Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. A fish walks into a bar and takes a seat. The bartender asks what he wants to drink, but the fish doesn’t say anything.

So the bartender asks, “What, cat got your tongue?” The fish grabs a cocktail napkin and writes out, No, actually, it was an isopod. An isopod got my tongue and by “got” I mean she ate it.

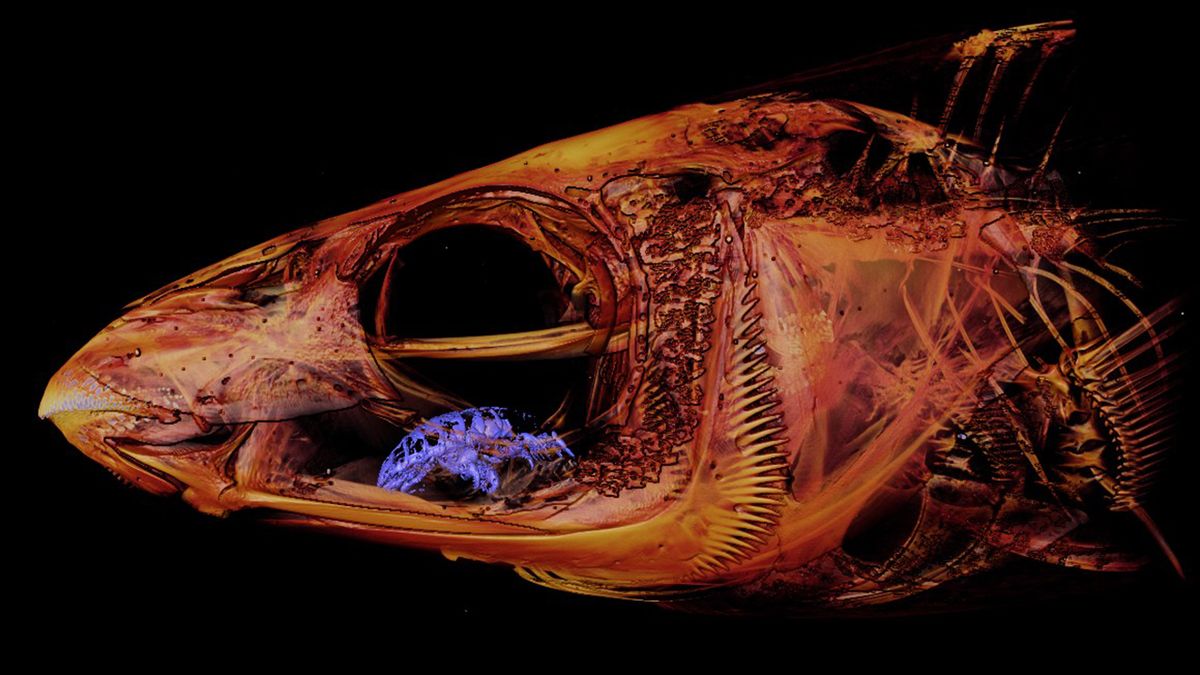

That joke may not be funny to you, but it’s hilarious to the tongue-eating isopod. You see, in the Gulf of California there actually exists a critter, Cymothoa exigua, that targets a fish by infiltrating its gills and latching onto its tongue. It proceeds to not only consume the organ, but will then replace it with its own body, providing the fish with a new fully functioning tongue it uses (probably a bit begrudgingly) to grind food against tiny teeth on the roof of its mouth.

This remarkable attack is the only known instance in the animal kingdom of a parasite functionally replacing an organ of its host. And while C. exigua targets several other fish, attaching to their tongues and draining their blood, only with the rose snapper does it devour and completely replace the organ as an operating structure, according to marine biologist Rick Brusca of the University of Arizona. And he stresses that while there are hundreds of such species of tongue-targeting isopods, contrary to many media reports, only C. exigua can actually truly assume the duties of the organ.

If you can believe it, this is a love story at heart. And the rose snapper’s face is the stage on which it unfolds.

These isopods are protandrous hermaphrodites: They first mature into males, but then switch sexes to become females. The magic starts when more than one C. exigua lands in a given fish’s gills. When the first one infiltrates it begins to mature into a male, but when the second one appears, said Brusca, it “stimulates the first one to change sex and become a female and crawl from the gills up through the throat and attach to the tongue, and then this new second one is the male that will impregnate her.”

The female next anchors herself to the tongue with seven pairs of legs, each tipped with a highly muscularized spine that looks a bit like a scorpion’s stinger. It is here where she’ll mate and spend the rest of her life experiencing the world as the snapper does, only, you know, without the excruciating pain.

As she grows, she molts just like any other arthropod and feeds on the snapper’s tongue not by gnawing away, but by sucking the blood out of it. “They have five sets of jaws,” said Brusca, “and all five of them are modified into these stiletto-like devices, and a couple of them are like long lances, if you will, that slice open the tissue of the host fish. And then the others operate together kind of like a soda straw to draw the blood up out of the wound that they’ve created.”

In this way C. exigua will slowly drain the life out of the snapper’s tongue, which atrophies from the tip on back, bit by bit, until nothing but the muscular stub remains. This the isopod now grasps with her rearmost three or four pairs of legs, essentially becoming the fish’s new tongue. And the isopod has likely evolved like this to keep her host alive, according to Brusca, allowing her more time to rear her young.

But once the tongue is gone, the female is left without a food supply. So as her young continue to develop, she lives solely on stored energy supplies, according to Brusca. Scientists aren’t yet sure at what point the young are released, or how exactly they find fish of their own, but Brusca reckons that the female may wait until her host is schooling with other fish to cut her offspring loose from the brood pouch, giving the young plenty of targets.

What happens next is like that scene in Titanic where the band goes down with the ship, except that those guys probably hadn’t been randomly switching sexes and eating fish tongues. With her procreation complete, the female isopod, who lost her ability to swim as she matured, “probably lets go and leaves or gets swallowed, but she’s out of the picture,” said Brusca. “And now you’ve got a fish with no tongue, so it’s not going to survive either. So it’s really a case of true parasitism. In fact, the fish ends up getting sacrificed for the sake of the isopod.”

>’It’s really a case of true parasitism. In fact, the fish ends up getting sacrificed for the sake of the isopod.’

It’s still not known quite why C. exigua goes so far in its parasitism of rose snappers, where in other species it merely sips from the tongue — not destroying it and taking over its job. “Maybe the tongue in the rose snapper is particularly susceptible,” said Brusca. “Maybe it doesn’t have as good a vascularization as other fish tongues.”

There’s still much to be learned here, but the advantages of such a lifestyle are clear: The female isopod not only gets a steady meal, but also a perfectly safe bunker in which to raise her young. Like any other creature, her purpose is to pass along her genes. And with her mission accomplished, she goes down with the ship.

Yet the snapper. The poor, poor snapper. Like many victims of parasites out there, it gets nothing but misery and blank stares and premature death. Which reminds me of a joke.

A rose snapper walks into a bar and slides in next to another rose snapper. The second snapper makes sexy eyes and asks what the newcomer’s name is, and the newcomer grabs a cocktail napkin and writes out, She Sells Sea Shells by the Sea Shore. The second snapper says, “Boy, what a tongue twister!” And the newcomer shifts nervously and averts her eyes. And the second snapper says, “What, isopod got your tongue?”

You may think that joke is crap, but isopods absolutely love it.

Src: wired.com