The discovery of a dozen new moons for Jupiter makes the king of planets the king of moons, too — at least for now.

The largest family of moons exists now on the largest planet in the solar system. Twelve previously unreported moons of Jupiter have had their orbits published by the Minor Planet Center (MPC) since December 20th. According to Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institute for Science, who just reported observations of the Jovian system made between 2021 and 2022, more publications are anticipated. The new discoveries raise the number of Jovian moons from 80 to 92, a significant 15% increase.

The additional objects are definitely in orbit around Jupiter, according to the MPC’s orbital calculations. The last “lost” Jovian moon, S/2003 J 10, was found thanks to additional information from Sheppard’s observations, and more recent observations prolonged its orbital path by another 18 years.

SATURN VS. JUPITERWith the recent discoveries, Jupiter now has a much larger lunar family than Saturn, which has 83 known moons. Saturn may overtake Jupiter in the near future, despite Jupiter now having the more moons. A search for objects that are traveling with the gas giants and are as small as 3 kilometers across discovered three times as many objects near Saturn as it did near Jupiter. A few hundred million years ago, a collision that upended a larger moon may have produced the more frequent Saturnian objects. (The fragments have not yet been traced thoroughly enough to be considered moons.)

If we could count all moons measuring at least 3 kilometers across, “Saturn would have more moons than all the rest of the solar system,” says Brett Gladman (University of British Columbia, Canada), who helped identify the new Saturnian objects but was not involved in the Jovian observations.

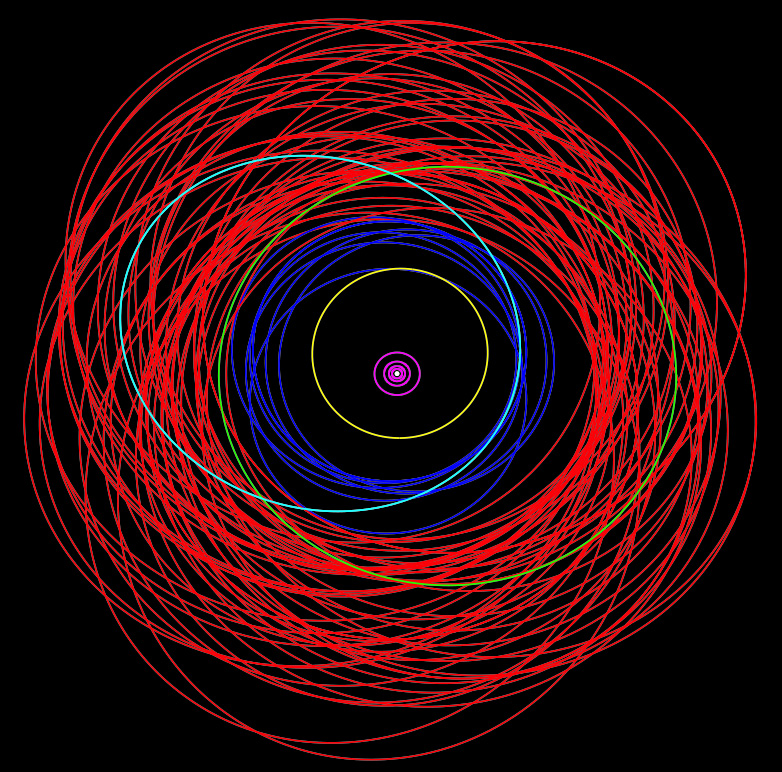

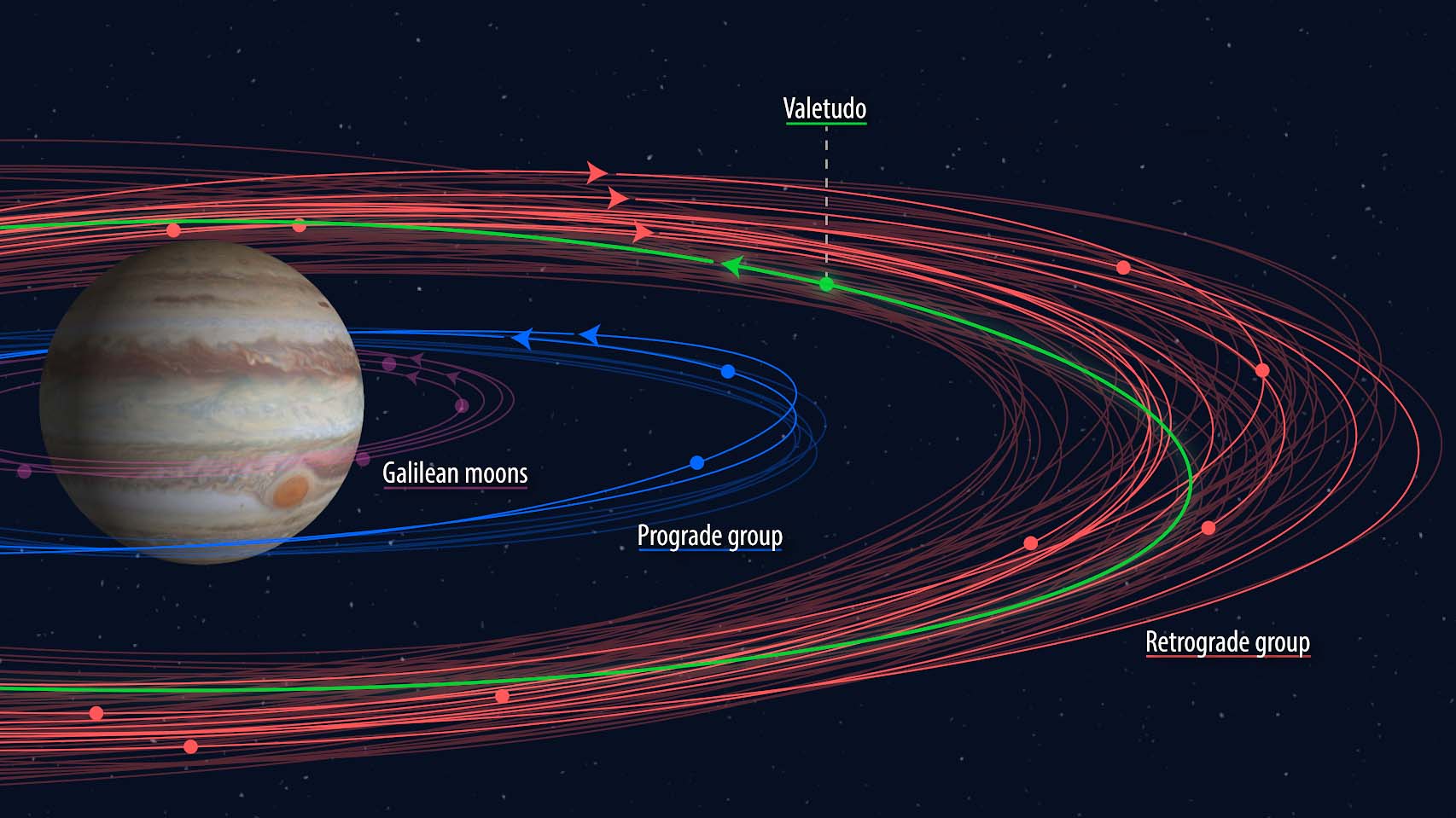

NEW MOONSAll of the newly discovered moons are small and far out, taking more than 340 days to orbit Jupiter. Nine of the 12 are among the 71 outermost Jovian moons, whose orbits are more than 550 days. Jupiter probably captured these moons, as evidenced by their retrograde orbits, opposite in direction to the inner moons. Only five of all the retrograde moons are larger than 8 kilometers (5 miles); Sheppard says the smaller moons probably formed when collisions fragmented larger objects.

Three of the newly discovered moons are in among 13 others that orbit in a prograde direction and lie between the large, close-in Galilean moons and the far-out retrograde moons. These prograde moons are thought to have formed where they are.

They’re harder to find than the more distant retrograde moons, though, says Sheppard. “The reason is that they are closer to Jupiter and the scattered light from the planet is tremendous,” he says. That light obscures them in the sky. Five were found before 2000, and only eight more have been discovered since then.

Besides the interest in their origins, these prograde moons could make suitable targets for a flyby from an upcoming mission. Three missions are in the works for the Jupiter system: the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE), scheduled for launch in April; N.A.S.A’s Europa Clipper , set for launch late next year; and a Chinese mission being considered for the 2030s.

BEYOND THE GALILEAN MOONSThe prograde objects outside the Galilean moons fall into two groups: the nine moons of the Himalia group orbit 11 to 12 million km from Jupiter, and the more distant duo in the Carpo group at 17 million km. The new discoveries added two of Himalia’s current tally of nine, and one of Carpo’s duo.

Searches for prograde moons outside these groups turned up nothing.

In the yawning gap between Himalia and the Galilean moons, there’s only one moon known: Themisto, a 9-kilometer object discovered by Elizabeth Roemer and Charles Kowal in 1975 but not recovered until 2000. It orbits 7.5 million kilometers (4.6 million miles) from Jupiter, roughly halfway between Callisto at 1.9 million km and the group of prograde moons starting at 11 million km.

That’s a big hole. “We have searched very deeply for objects near Themisto, and have found nothing else to date,” says Sheppard. He says glare from Jupiter is so strong it would hide anything smaller than 3 kilometers across.

A single prograde moon, the 1-km Valetudo, orbits beyond the Carpo group, at 19 million km from Jupiter. After discovering it in 2018, Sheppard called Valetudo an “oddball” because its orbit crosses those of a few retrograde moons. This highly unstable situation is likely to lead to head-on collisions that would shatter one or both objects. Sheppard adds that Valetudo might be all that remains of a larger prograde moon that had suffered from earlier collisions. No other members have been found to date.

DISCOVERING NEW MOONSDiscoveries of small moons of Jupiter or Saturn are typically reported in Minor Planet Center Electronic Circulars. But those reports take time.

Analyzing observations and calculating trajectories is more complex for planetary moons than for asteroids or comets, because a moon’s path depends on both the gravity of its planet as well as the Sun. Observations must also track the moon for a full orbit to show it really orbits the planet, and the outer moons of Jupiter take about two years to orbit the planet. For asteroids and comets, on the other hand, a few weeks of observations may suffice to predict their course because their path depends only on the Sun.

We can expect more reports as Sheppard, Gladman, and others continue the hunt for new moons in the outer solar system.