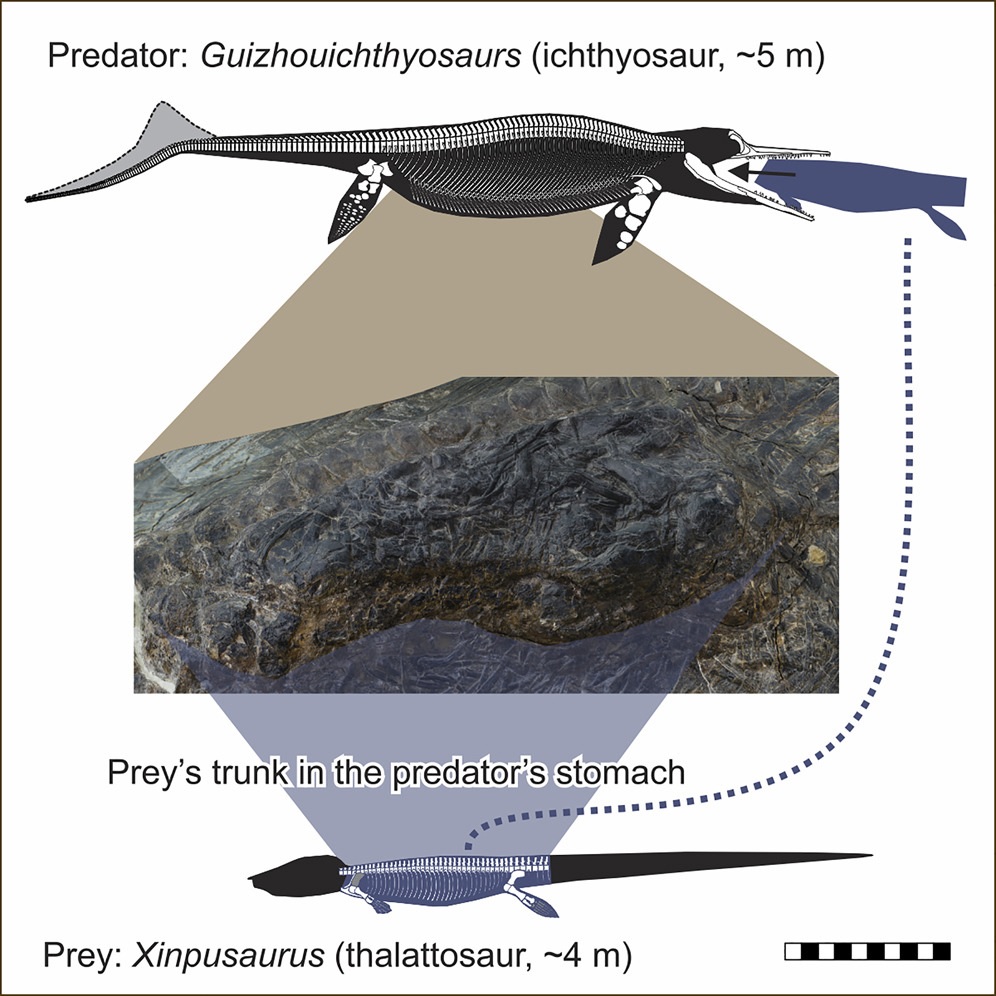

The evidence comes from a team of U.S. scientists who found remnants of a prehistoric clash in a slab of rock at the Chinle Formation in New Mexico. The battle, which occurred in the Triassic period about 210 million years ago, involved a semi-aquatic crocodile-like dinosaur called phytosaur and a large reptile called rauisuchid, and ended with the tooth of the former embedded in the bone of the latter.

A partial left femur of rauisuchid with embedded phytosaur tooth; scale bar next to complete fossil – 10 cm; scale bars in magnified photographs – 1 cm. Image credit: Stephanie K. Drumheller et al.

About 210 million years ago when the supercontinent of Pangea was starting to break up, phytosaurs and rauisuchids were apex predators (at the top of the food chain).

It was widely believed these two predators didn’t interact much as phytosaurs were kings of the water, and rauisuchids roamed the land. But those ideas are changing, thanks largely to the contents of a single bone.

“To find a phytosaur tooth in the bone of a rauisuchid is very surprising,” said Dr Stephanie Drumheller of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, a team member and the lead author of a paper published in the journal Naturwissenschaften.

“These rauisuchids were the largest predators in their environments. You might expect them to be the top predators as well, but here we have evidence of phytosaurs, who were smaller, semi-aquatic animals, potentially targeting and eating these big carnivores.”

Reconstruction of the interaction of a rauisuchid and a phytosaur about 210 million years ago. Image credit: Christopher Hayes / Virginia Tech.

Dr Drumheller and her colleagues studied the bone of a rauisuchid and the phytosaur tooth using their 3D printed copies and CT scans.

This, along with an analysis of bite marks, revealed that the animal was preyed upon at least twice over the course of its life, by phytosaurs.

“Phytosaurs were thought to be dominant aquatic predators because of their large size and similarity to modern crocodylians, but we were able to provide the first direct evidence they targeted both aquatic and large terrestrial prey,” said co-author Dr Michelle Stocker from Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

“This research will call for us to go back and look at some of the assumptions we’ve had in regard to the Late Triassic ecosystems.”

“The distinctions between aquatic and terrestrial distinctions were over-simplified and I think we’ve made a case that the two spheres were intimately connected,” the scientist concluded.

Source: sci.news