The city of Heracleion was swallowed by the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Egypt nearly 1,200 years ago. It was one of the most important trade centers in the Mediterranean before it sank more than a millennium ago. For centuries, the existence of Heracleion was believed to be a myth, much like the city of Atlantis is viewed today. But in 2000, the underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio finally found the sunken city after extensive underwater research in today’s Aboukir Bay.

Before this modern-day discovery, Heracleion had been all but forgotten, relegated to a handful of inscriptions and phrases in ancient texts by the likes of Strabo and Diodorus. The Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BC) writes of a great temple that was built where the mythological hero Heracles (or Herakles) first set foot in Egypt. He also claimed that Helen of Troy and Paris visited the city before their famous Trojan War. Four centuries after Herodotus visited Egypt, the Greek geographer Strabo noted that the city of Heracleion was located to the east of Canopus at the mouth of the River Nile.

Franck Goddio founded the European Insтιтute for Underwater Archaeology, and together they discovered the long-lost city of Heracleion off the coast of Egypt. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Franck Goddio: The Hunter of Lost Cities Discovers Heracleion

The underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio is known as “a pioneer of modern maritime archaeology.” Goddio founded the European Insтιтute for Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) in 1987, with the aim to explore and research underwater archaeological sites. IEASM is known for having developed a systematic approach, using geophysical prospecting techniques on underwater archaeological sites. By exploring the area in parallel straight lines at regular intervals, the team can identify anomalies on the sea floor, which can then be explored by divers or robots.

In 1992, IEASM began mapping the area around the port of Alexandria and in 1996 they extended their research to include Aboukir Bay, tasked by the Egyptian government to discover Canopus, Thonis and Heracleion, all believed to have been reclaimed by the Mediterranean Sea. This research allowed them to understand the topography and circumstances that caused submersion of the area over time. The team used information from historical texts to establish the areas of primary interest. The survey of Aboukir Bay covered a research area of 11 by 15 kilometers (6.8 x 9.3 miles).

Beginning in 1996, the mapping of the Aboukir Bay took years. In 1999 they discovered Canopus, and in 2000 they discovered Heracleion. The site of the sunken city of Heracleion remained hidden in the Bay of Aboukir for so long because the remains of the ancient city are covered with sediment. The upper layer of the sea floor is made up of sand and silt deposited as it exits the River Nile . The team from IEASM was able to locate remains by creating detailed magnetic maps, which provided the evidence needed to finally pinpoint the location of Heracleion.

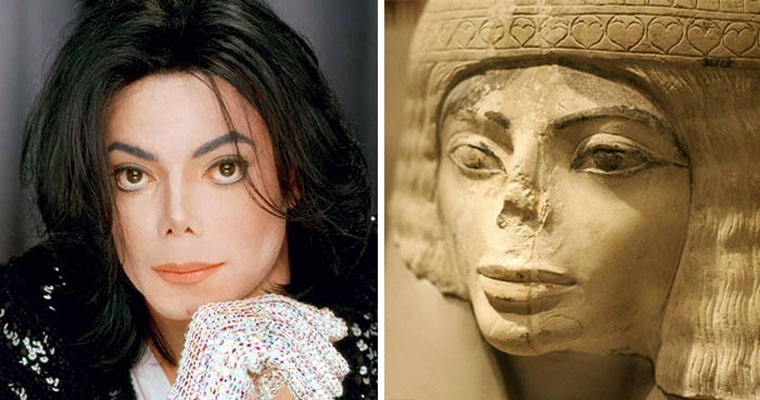

One of the most impressive finds at the sunken city of Heracleion in the Bay of Aboukir was the statue of a Ptolemaic era queen. It probably represented Cleopatra II or Cleopatra III, dressed as the goddess Isis. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Finding Heracleion: A Lost City Under the Sea?

Now submerged under the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, in its heyday Heracleion was located at the mouth of the River Nile, 32 km (20 miles) to the northeast of Alexandria in ancient Egypt . The enormous city was an important port for trade with Greece, as well as a religious center where sailors would dedicate gifts to the gods. The city was also politically significant, with pharaohs needing to visit the temple of Amun to become universal sovereign.

Using cutting edge technology, and in collaboration with the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, IEASM managed to locate, map, and excavate the ancient sunken city of Heracleion, which was found 10 meters (32.8 ft) below water and 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) from the current-day coastline in the western part of Aboukir Bay.

After removing layers of sand and mud, divers uncovered the extraordinarily well preserved city with many of its treasures still intact. These included the main temple of Amun-Gerb, giant statues of pharaohs, hundreds of smaller statues of gods and goddesses, a sphinx, 64 ancient shipwrecks, 700 anchors, stone blocks with both Greek and ancient Egyptian inscriptions, dozens of sarcophagi, gold coins, and weights made from bronze and stone.

The team discovered a sunken statue of a pharaoh on the Mediterranean sea floor near the great temple of ancient Heracleion. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

The Remains of Heracleion: Vestiges from a Lost World

Amongst the remains of the once great city, the underwater archaeologists discovered an enormous 5.4 meter (17.7 ft) statue of Hapi, the god dedicated to the inundation of the Nile. This was one of three colossal red granite sculptures discovered dating back to the 4th century BC. In 2001 the team also discovered an ancient stele originally commissioned by Nectanebo I some time between 378 and 362 BC, complete with detailed and clearly readable inscriptions.

The inscriptions on this ancient stele allowed the archaeologists to determine that the ancient cities of Thonis and Heracleion were in fact one in the same, Thonis being the name used originally by the Egyptians, and Heracleion being the ancient Greek name. From then on the ancient sunken city was known as Thonis-Heracleion.

View of the giant triad of 4th century BC red granite statues discovered in the underwater sunken city of Thonis-Heracleion. They represent a pharaoh, his queen, and the god Hapi. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Spectacular pH๏τographs of the discovery and recovery process reveal numerous statues and structures that once stood tall and mighty in the great city. One pH๏τo shows a Greco-Egyptian statue of a Ptolemaic queen which stands eerily on the seabed, surrounded only be sediment and darkness, while another pH๏τograph shows the face of a great Pharaoh peering up out of the sand.

In an interview with the BBC in 2015, Franck Goddio explained that the policy of the IEASM underwater excavations was “to learn as much as we can by touching as little as we can and leaving it for future technology.” At that point around 2% of the site had been excavated. The clay sediment from the Nile which has hidden the ancient city for so long also acts to protect the artifacts on the sea floor from the salt water.

In the case of artifacts which are removed from their hidden underwater sanctuary, IEASM takes a great deal of care to restore and preserve them on board their ships and in laboratories. In some cases, this has taken days, but in others, such as that of the enormous Hapi statue, this took two-and-a-half years.

Bronze oil lamp discovered in the temple of Amun in the sunken city of Heracleion. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Understanding Why Cites Sink into the Sea

Built on the Nile Delta, the city itself was traversed by a vast network of canals and was said to be stunningly beautiful. Dubbed the Venice of the Nile, Heracleion was at one point the largest port in the Mediterranean. Explorations of the site have concluded that the city probably gradually declined in importance as it slipped into the sea during the second half of the 8th century AD. This begs the question of why such a significant city was lost.

The causes include a series of geological phenomena and cataclysmic events. IEASM joined forces with other insтιтutions to conduct geological research which has shown that the southeastern basin of the Mediterranean was affected by slow subsistence, the rise in sea levels, and local phenomenon related to the consтιтution of the soil in the area, which together formed the conditions for cities such as Heracleion to sink into the sea.

Digital reconstruction of what Heracleion may have looked like. (Yann Bernard / Hilti Foundation )

Exhibitions of Egypt’s Lost Worlds

In 2005, IEASM attained permission from the Egyptian authorities who own the artifacts to arrange a touring exhibition of the artifacts discovered. The resulting exhibition, enтιтled Egypt’s Sunken Treasures, toured major cities in Germany, Spain, Italy, and Japan. The exhibition at the Grand Palais in France averaged a record 7,500 visitors per day.

The British Museum joined forces with Franck Goddio in 2015 to arrange its first underwater archaeology exhibition, which included about 200 artifacts discovered off the coast of Egypt by IEASM between 1996 and 2012. By then Goddio estimated that they had explored only about 5% of the ancient city of Heracleion, estimated to cover an area of about 3.5 sq. km (1.35 miles).

According to The Art Newspaper , Goddio stated that “this would be a big undertaking on land, but under the sea and under the sediment, it’s a task that will take hundreds of years.” To understand the scale of this task, Heracleion is about three times the size of Pompeii and archaeologists have been excavating that particular catastrophic site for over 100 years.

The exhibition at the British Museum, enтιтled Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds , was also presented at the Insтιтut du Monde Arabe in Paris in 2015, and the Saint Louis Art Museum in the United States. Its last stop was the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts up until January 2021, before the artifacts returned to Egypt.

The discovery of Heracleion raises important questions about whether so-called “mythical cities” exist in reality. If a city once believed to be myth can be uncovered from the depths of the sea, who knows what others legendary sunken cities of the past will be uncovered in the future? Only time will tell.

Source: pahilopahilonews