New radiocarbon dates on American mastodon (Mammut americanum) fossils in Alaska and Yukon (eastern Beringia) suggest this species suffered local extinction tens of millennia before either human colonization – the earliest estimate of which is between 13,000 and 14,000 years ago – or the onset of climate changes at the end of the Ice Age about 10,000 years ago, when it was among 70 species of mammals to disappear in North America.

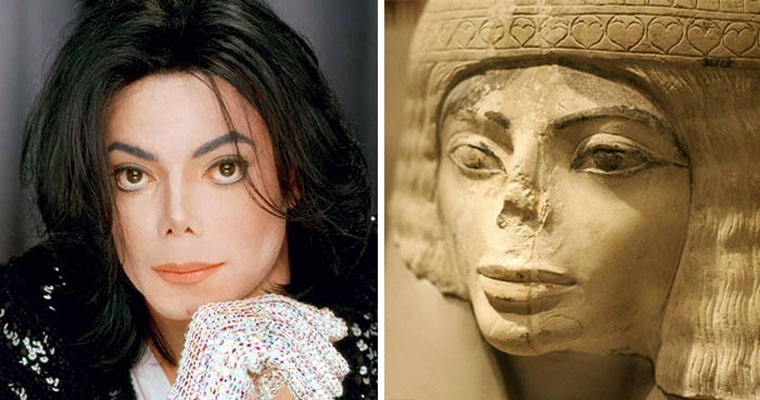

Some 125,000 years ago, during a warm interval known as the last interglaciation, megafaunal mammals were able to penetrate parts of northern North America that had previously been covered by massive ice sheets. In this reconstruction, in addition to the American mastodon (Mammut americanum), illustrated is the Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii), the flat-headed peccary (Platygonus compressus), and the western camel (Camelops hesternus). Image credit: © George ‘Rinaldino’ Teichmann.

“Scientists have been trying to piece together information on these extinctions for decades. Was it the result of over-hunting by early people in North America? Was it the rapid global warming at the end of the ice age? Did all of these big mammals go out in one dramatic die-off, or were they paced over time and due to a complex set of factors?” said Dr Ross MacPhee of the American Museum of Natural History, who is a co-author of the paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Mastodons are members of the group of mammals called proboscideans, which was once much more diverse and widespread. Only two species survive today, the African and Asian elephants, both threatened with extinction.

Mastodons roamed widely over continental North America as well as peripheral locations like the tropics of Honduras and the Arctic coast of Alaska for roughly 3.5 million years before it finally became extinct about 10,000 years ago. They were browsing specialists that relied on woody plants and lived in coniferous or mixed woodlands with lowland swamps.

“Mastodon teeth were effective at stripping and crushing twigs, leaves, and stems from shrubs and trees. So it would seem unlikely that they were able to survive in the ice-covered regions of Alaska and Yukon during the last full-glacial period, as previous fossil dating has suggested,” said lead author Dr Grant Zazula of the Government of Yukon’s Palaeontology Program.

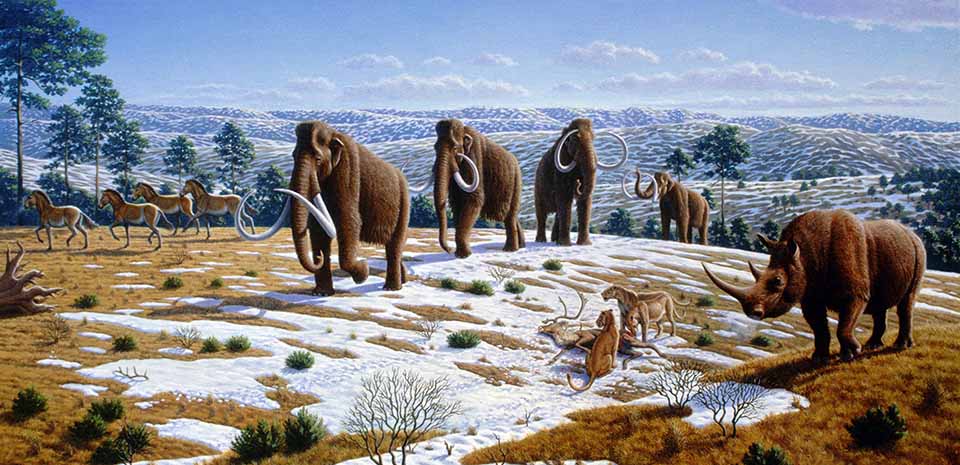

This illustration shows a reconstruction of an American mastodon (Mammut americanum) at the top; below is a comparison between an American mastodon and a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Image credit: © George ‘Rinaldino’ Teichmann.

The scientists used two different types of precise radiocarbon dating on a collection of 36 fossil teeth and bones of American mastodons.

The dating methods are designed to only target material from bone collagen, not accompanying ‘slop,’ including preparation varnish and glues that were used many years ago to strengthen the specimens.

All of the fossils were found to be older than previously thought, with most surpassing 50,000 years, the effective limit of radiocarbon dating.

When taking mastodon habitat preferences and other ecological and geological information into account, the results indicate that mastodons probably only lived in the Arctic and Subarctic for a limited time around 125,000 years ago, when forests and wetlands were established and the temperatures were as warm as they are today.

“The residency of mastodons in the north did not last long. The return to cold, dry glacial conditions along with the advance of continental glaciers around 75,000 years ago effectively wiped out their habitats,” Dr Zazula said.

“Mastodons disappeared from Beringia, and their populations became displaced to areas much farther to the south, where they ultimately suffered complete extinction about 10,000 years ago.”

Source: sci.news