This week, a trio of sizable asteroids—including two that N.A.S.A has classified as “potentially hazardous”—will pass Earth’s orbit around the sun. This is what that implies.

There are millions of rogue space rocks in our solar system, and this week three especially large ones will fly by Earth. Don’t fret, though; N.A.S.A estimates that the closest one will still miss Earth by a comfortable 2.2 million miles (3.5 million kilometers), or about 10 times the typical distance between Earth and the moon.

Asteroid 2012 DK31 will pass our globe on February 27 at a distance of about 3 million miles (4.8 million km). The asteroid crosses Earth’s orbit every few years and is believed to be 450 feet (137 meters) across, or roughly the width of a 40-story skyscraper.

Although the space rock poses no imminent threat to Earth, N.A.S.A classifies it as a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) – meaning the rock is large enough and orbits close enough to Earth that it could cause serious damage if its trajectory changed and a collision occurred. Generally, any asteroid measuring greater than 450 feet wide and orbiting within 4.6 million miles (7.5 million km) of Earth is considered a PHA. (N.A.S.A has mapped this asteroid’s trajectory for the next 200 years, and no collisions are predicted to occur).

On Tuesday (Feb. 28) a second skyscraper-sized PHA, also measuring roughly 450 feet across, will cross our planet’s orbit at a distance of about 2.2 million miles (3.5 million km). Known as 2006 BE55, this chunky space rock’s orbit crosses Earth’s orbit every four or five years.

Finally, on Friday (March 3), an asteroid measuring roughly 250 feet (76 m) across will fly by at a distance of 3.3 million miles (5.3 million km). The rock, named 2021 QW, isn’t quite wide enough to qualify as a PHA, but still makes a relatively close approach to Earth every few years.

Why do scientists pay such close attention to space rocks that will miss our planet by millions of miles? Because even slight changes to an asteroid’s trajectory – say, from being nudged by another asteroid or influenced by the gravity of a planet – could send nearby objects like these on a direct collision course with Earth.

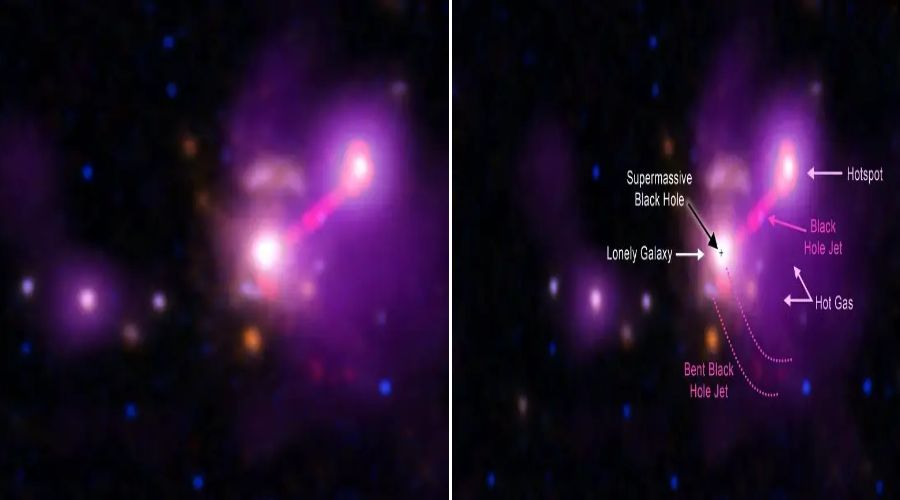

Fortunately, N.A.S.A’s calculations show that no known asteroids are currently on a path to hit Earth any time for at least 100 years. Should a large asteroid one day pose a direct threat to our planet, astronomers are already working on methods to thwart it. That was the motivation behind N.A.S.A’s recent Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which intentionally smashed a rocket into an asteroid to alter its orbital speed. The mission did not destroy its target outright, but did prove that head-on rocket attacks are capable of changing a space rock’s orbital parameters in significant ways.