A new species of ichthyosauriform marine reptile that lived about 248 million years ago (Early Triassic) has been identified from fossils found in Anhui Province of China.

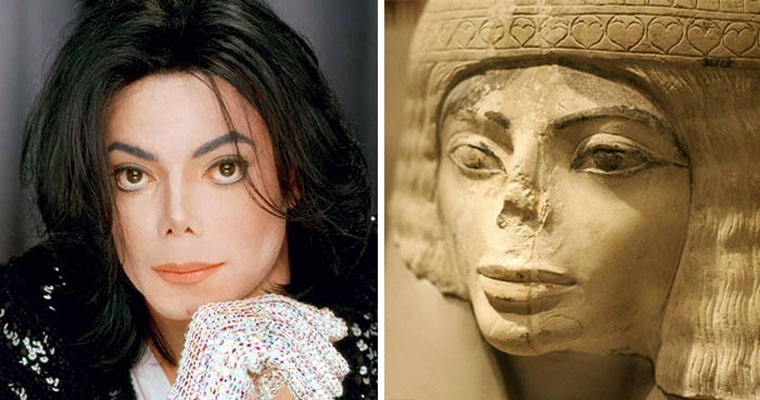

Sclerocormus parviceps. Image credit: Da-Yong Jiang.

Ichthyosaurs were a successful group of marine animals that flourished in the world’s oceans of the Mesozoic era.

Most of them looked a little bit like today’s dolphins. They were well adapted to feed in water, with a long, narrow, and often graceful snout armed with teeth.

But the new species, scientifically named Sclerocormus parviceps, is a strange anomaly in the ichthyosaur world.

It measured about 5.3 feet (1.6 m) long, including a 3 foot (92 cm) long tail. It had a short snout and, instead of a tail with triangular flukes (think of a fish’s tail-fins), it had a long, whip-like tail without big fins at the end.

And while many ichthyosaurs had conical teeth for catching prey, the new species was toothless and instead seems to have used its short snout to create pressure and suck up food like a syringe.

“Sclerocormus parviceps tells us that ichthyosauriforms evolved and diversified rapidly at the end of the Lower Triassic period,” said Dr. Olivier Rieppel of the Field Museum.

“We don’t have many marine reptile fossils from this period, so this specimen is important because it suggests that there’s diversity that hasn’t been uncovered yet.”

The way Sclerocormus parviceps evolved into such a different form so quickly sheds light on how evolution actually works.

“It has been considered that early Mesozoic marine reptiles evolved slowly in the Early Triassic after the end-Permian mass extinction, contrary to the fast radiation of most metazoans during the same time interval,” Dr. Rieppel and co-authors said.

“The present and other recent discoveries of Early Triassic marine reptiles indicate that the diversification of Triassic marine reptiles was not a single phase of unbroken increase in diversity. There were at least two waves of marine reptile diversification, separated by a taxonomic bottleneck near the Early-Middle Triassic boundary.”

Marine reptiles like Sclerocormus parviceps that lived just after the end-Permian mass extinction also reveal how life responds to huge environmental pressures.

“We’re in a mass extinction right now, not one caused by volcanoes or meteorites, but by humans,” Dr. Rieppel said.

“So while the extinction 250 million years ago won’t tell us how to solve what’s going on today, it does bear on the evolutionary theory at work.”

Source: sci.news