And it really doesn’t look like we’re prepared for it

Illustration licensed from Shutterstock

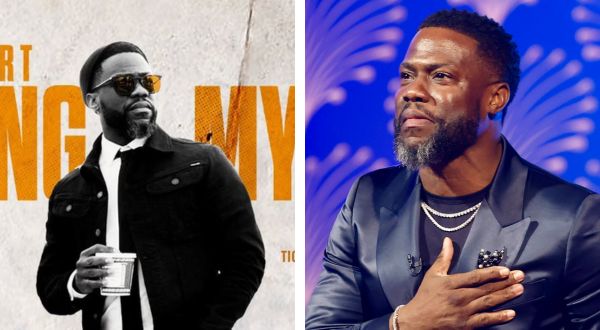

If you use Facebook or Instagram, you might’ve recently come across a sexually suggestive ad featuring the English actress Emma Watson.

But although it does look like her, it’s not her.

Watson’s face was swapped into a video of another woman bending in front of a camera, about to engage in a sexual act. And a company behind a deepfake face-swap app that created it — which lets you do the same thing with any face in any video of your choosing — then used it to promote their product.

According to NBC news, it was part of a massive campaign that included 127 videos featuring Watson’s likeness and another 74 similarly provocative clips featuring another famous female celebrity — Scarlett Johansson.

The ad campaign — which was viewed by millions of people — is now apparently removed from all Meta platforms.

And the app has vanished from both Apple and Google Play stores.

But if you go on either of these and type in ‘deepfake,’ you’ll find quite a few other apps promising to do the exact thing.

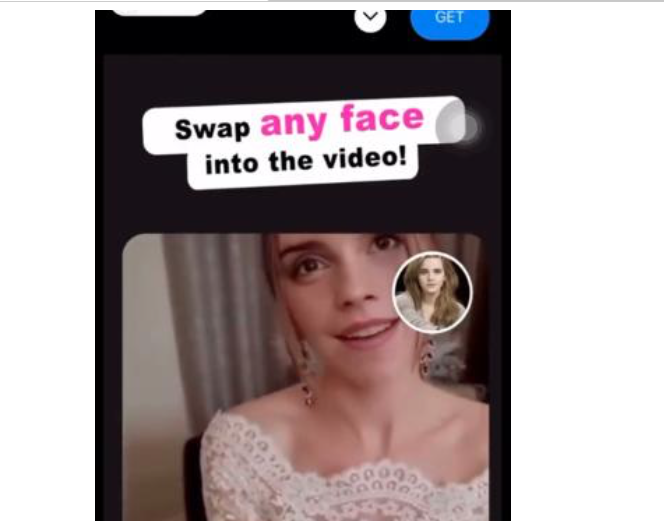

However, although deepfakes — content where faces or sounds are switched out or manipulated — have been overwhelmingly used to make non-consensual porn in recent years, as the technology has improved and become more widespread, it started to be applied in different ways, too.

Not only to make sexually explicit videos but also to spread false information, create further divisions and even… scam people.

The blurring line between fact and fiction

In the last month or so, I came across a couple of viral deepfake videos circulating across different social media platforms.

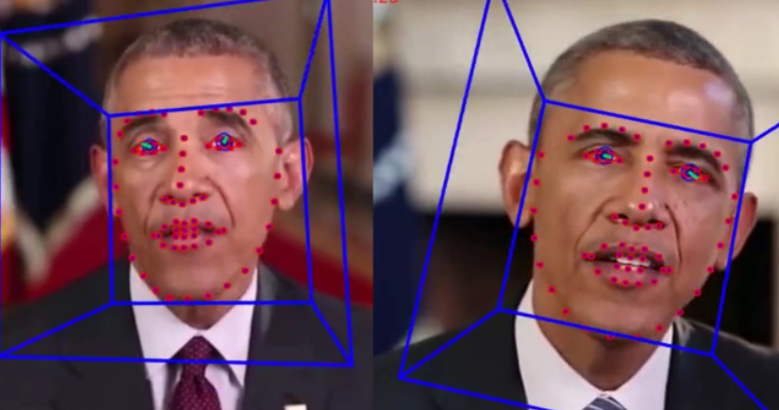

One was a speech by the current British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, talking about… queuing up for McDonald’s and playing video games. Even though it does look semi-realistic, after the first few seconds you can tell it’s clearly a parody. And a deepfake.

But another one definitely had me fooled, at least at first.

It’s a video of the comedian turned misinformation peddler Joe Rogan discussing a ‘libido-boosting’ coffee brand for men with one of his guests, Dr Andrew Huberman. And since it wouldn’t be entirely out of character for him, and it looked pretty real, too, I thought it was just a weird brand deal.

A quick scroll through the comments made me realise I was wrong. But it also got me thinking that I’ve probably seen more videos like this lately; I just haven’t realised it at the time.

And so I went digging for more viral manipulated content and, unsurprisingly, found quite a lot of it.

A few months ago, a video of US Vice President Kamala Harris saying that everyone hospitalised for Covid-19 was vaccinated was making rounds on Tik Tok. (In the original video, she said the patients were unvaccinated.)

Last month, a digitally altered video of US President Joe Biden calling for a national draft to fight the war in Ukraine was shared as authentic by several large conservative Twitter accounts. Some of them even labelled it as ‘breaking news’.

More recently, a video titled ‘Bill Gates caught in corner’ which shows him being accused of stealing Microsoft software and promoting the COVID-19 vaccine to make money, and then abruptly ending the interview, has also gone viral on multiple social media platforms.

But it’s not only high-profile individuals whose videos or audio are being manipulated to seem like they’re doing and saying things they’ve never actually said or done.

It’s regular people, too.

A few weeks ago, a group of American high schoolers made a deepfake video of their principal making virulently violent and racist remarks about Black students and then posted it on Tik Tok.

And all that, it’s just on top of all the non-consensual deepfake porn content that has been circulating all over the internet for years now.

Deepfakes can be quite harmful — and sometimes they are

Most people probably know that you can’t believe everything you see — particularly on the internet. After all, it’s been a hotbed of fake news, hoaxes and other types of misinformation practically since its inception.

At this point, I hope everyone is also aware that Photoshop and other photo-editing softwares can create highly realistic images of situations or things that never happened or existed.

Videos and audio recordings, though, are a whole different story.

And I’d probably even go as far as to say that most of us don’t realise how much they can be manipulated.

Because up until recently, you couldn’t make a realistic deepfake video or audio of someone else without elaborate software and fairly sophisticated computational know-how. But today, many tools to create them are available to everyday consumers — even on smartphone apps, and often for little to no money.

In addition to deepfake tools that let you superimpose any face over any body — including those of adult movie stars — there are a few speech-cloning ones that can be trained to convincingly simulate a person’s voice and even some that can do it with celebrity voices.

And they’re not only easily accessible and cheap but can produce moderate to high-quality deepfake results that could be used to successfully fool others.

Well. It’s not exactly difficult to predict how all of that could be weaponised by internet trolls, misinformation peddlers or even journalists to spread misinformation, set off unrest, incept a political scandal, discredit public figures or harass people.

And to some extent, it already has.

Non-consensual deepfake ‘sex tapes,’ for instance, have already been used to silence, degrade and harass women. To hurt their interpersonal relationships, reputation, mental health and job prospects. As a result, some had to change their names. And some others had to remove themselves from the internet out of fear of being re-traumatised.

There have also been many recent scams involving deepfake voice technology. Last year, it was actually the most frequently reported type of fraud in the US, and it generated the second-highest losses for those targeted — around $11 million in total.

And if all that weren’t enough, according to a report by Graphika, a New York-based cyber research firm, there’s even been one recent instance of the use of deepfake technology in what appeared to be a pro-Chinese propaganda campaign.

In one of the videos they analysed, a Wolf News broadcaster seems to applaud China’s role in geopolitical relations at an international summit meeting.

Only there’s no such a news outlet as ‘Wolf News’.

And the anchor isn’t even a real person — it’s just a digital puppet.

We really aren’t prepared to deal with a wave of digital fakes

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/metroworldnews/FTRJ6ZLI3RDOVJ6KJH54A76CUU.webp)

In theory, most — if not all — social media platforms now prohibit deepfakes and any content doctored in a misleading way. But they clearly aren’t very good at detecting it just yet.

The deepfake ad featuring Emma Watson stayed on Meta’s platforms for quite some time before it was removed. And many of the deepfake videos I mentioned earlier were never even removed.

Still, you’d think that given how easy, cheap and quick it is to manipulate media nowadays — and how fast this technology will likely improve in the next few years — it would make sense for the biggest tech companies to build up their teams tasked with ethics, content moderation, hate speech, etc.

But judging by recent massive layoffs in the sector, they seem to be doing the exact opposite — tearing them down.

That already happened a few months ago at Twitter, right after Elon Musk took over. And more recently, also at Microsoft.

Perhaps they’ll eventually replace those teams with deepfake detection tools, which are still in relatively early stages of development. Perhaps not. Either way, it’s pretty naive to hope that they will act in the best interest of humanity on this one.

After all, social media giants thrive on hate and polarisation, which can get infinitely worse if you sprinkle it with a generous amount of manipulative and malicious deepfakes.

(And, in turn, help them make even more money.)

Legally speaking, there isn’t much to be done about the growing digital fakery either. For now, only a handful of countries have some laws addressing deepfake media, but not really prohibiting them entirely.

So even if someone were to superimpose your face into a porn scene or create a deepfake of you saying things you’d definitely never say and then distribute it all over the internet or to your friends and family, you’d be left with little to no legal recourse.

And if it went viral, you probably wouldn’t even be able to remove it from the internet.

Whether we like it or not, deepfakes are here to stay.

And they will likely only become more realistic as the AI technology used to make them becomes increasingly powerful.

But while it’s a good rule of thumb not to take anything at face value or rely on just one source of information, without a push for better education about media literacy and better standards for the online world in general, it’s only going to become harder to know what is true or false.

The internet might be a great place for many things.

But it’s not nearly as much about conveying the truth as it’s about making money.

Let’s not forget that.

Src: medium.com