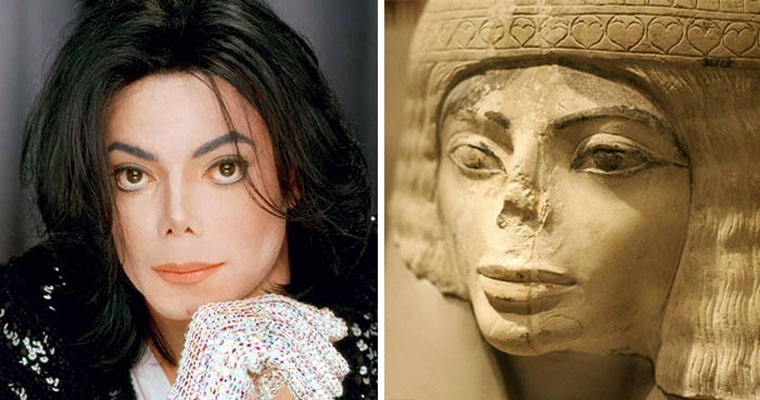

Macronectes tinae lived approximately 3 million years ago (Pliocene period), and belongs to the extant genus Macronectes.

An artistic reconstruction of Macronectes tinae in its paleoenvironment; a darker plumage was chosen for the reconstruction because a darker coloration in giant petrels seems to be related to warmer regions, as Taranaki had warmer temperatures during the Pliocene period. Image credit: Simone Giovanardi / Te Papa.

Giant petrels are the largest birds in the family Procellariidae (petrels and shearwaters), identifiable by their heavyset body and beak.

They are represented by two living species: Macronectes giganteus and Macronectes halli.

Both are distributed around the southern hemisphere, ranging from Antarctica to the subtropics.

The newly-identified species, named Macronectes tinae, is the first fossil Macronectes ever reported.

“Giant petrels are very distinctive birds, being the size of small albatrosses, with huge bulbous beaks,” said Dr. Alan Tennyson from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Dr. Rodrigo B. Salvador from the Arctic University of Norway.

“They are famous for their habit of following ships and their outrageous scavenging activities — sometimes getting fully immersed in the carcass of some poor creature, ripping it apart and becoming covered in blood and other goo.”

“While their taste may be questionable to us, they perform a useful role as marine cleaners.”

“We find them endearing birds, with their unique look and distinctive musty smell. In contrast to their brazen behavior fighting over carrion, towards people on land they are timid and wary.”

“Like most kinds of petrels, they spend their lives roaming the oceans.”

“For nesting, they maintain long-term partners, with which they share the duties of raising a single chick each year.”

The only two fossils known of Macronectes tinae were recovered in the coastal deposits of the Tangahoe Formation, South Taranaki, New Zealand.

“They consist of a fragmentary left humerus and a nearly complete skull, which in all likelihood belonged to distinct individuals because the humerus was found about 2 km south of the skull,” the paleontologists said.

In their study, they analyzed the new Macronectes fossils and compared them to the skeletons of living giant petrels.

They found that the ancestral giant petrels were smaller and had wing bones with features intermediate between living giant petrels and their closest relatives.

“Macronectes tinae is morphologically similar to the two present-day Macronectes species, but it was a smaller bird,” they said.

“The skeletal differences between them are easily observable and sufficient to establish a new extinct species.”

“The functional significance (if any) of these differences, however, remains unknown.”

“The Tangahoe Formation continues to provide outstanding seabird fossils and is becoming an important piece of the puzzle to understand the evolution and biogeography of seabirds in New Zealand and beyond,” they concluded.

“New Zealand, in particular, is considered a global center of procellariiform diversity, a status that was probably already in place in the Late Pliocene.”

Source: sci.news