Black holes are powerful power plants in space. They give quasars and other active galactic nuclei the energy they need to shine (AGNs). This is because of how matter and its huge gravitational and magnetic forces work together.

Technically, a black hole doesn’t have a magnetic field, but the dense plasma that makes up the accretion disc around it does. As plasma spirals around a black hole, the charged particles inside it create an electric current and a magnetic field.

Since the direction of plasma flow doesn’t change on its own, it’s likely that the magnetic field is pretty stable. Imagine how surprised the scientists were when they found proof that a black hole’s magnetic field had changed direction.

One way to think about a magnetic field is as a magnet with a north pole and a south pole. When the direction of the imaginary pole and the magnetic field both change, this is called a magnetic reversal. This is a common thing for stars to do.

Scientists have known about the 11-year cycle of sunspots since the 1600s. This cycle is caused by the Sun’s magnetic field, which changes direction every 11 years. Even the Earth’s magnetic field switches directions every few hundred thousand years or so. But supermassive black holes were not thought to be likely to have magnetic reversals.

In 2018, a computerized scan of the sky found a sudden change in a galaxy 239 million light-years away. The galaxy called 1ES 1927+654 is now 100 times brighter than it was before.

Soon after it was found, Swift Observatory caught it giving off x-rays and ultraviolet light. Archival data from the area showed that the galaxy started to get brighter near the end of 2017.

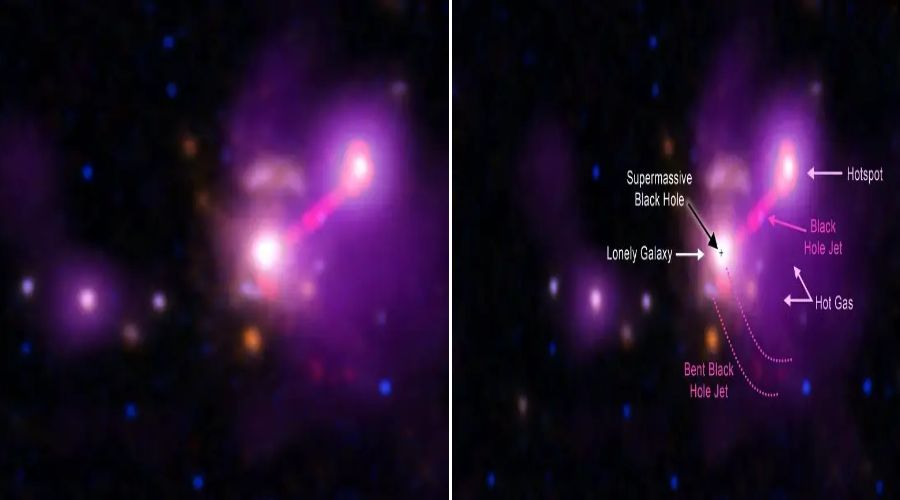

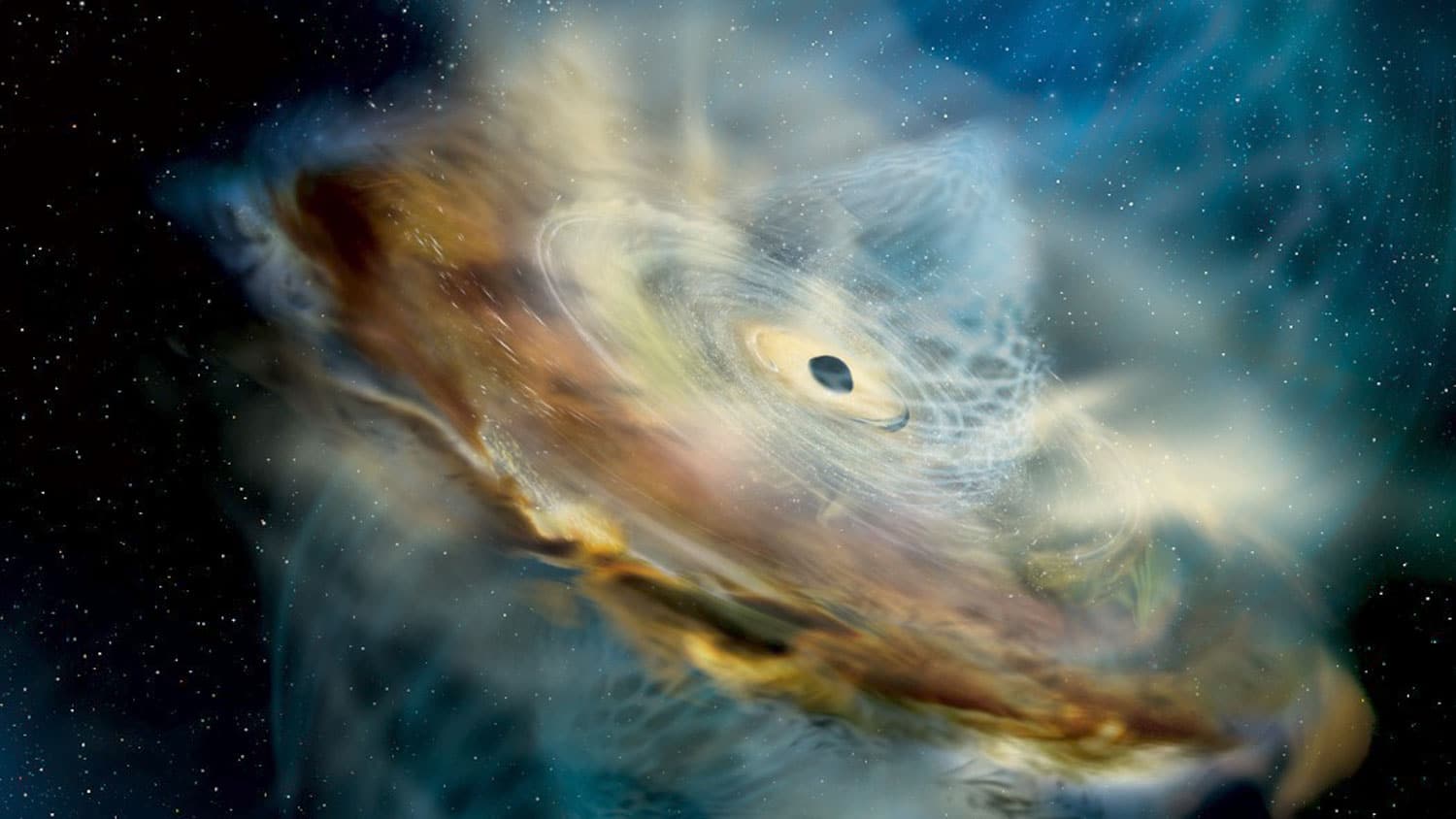

How a black hole might undergo magnetic reversal. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Jay Friedlander

At the time, people thought that this sudden brightening was caused by a star moving close to the supermassive black hole in the center of the galaxy. A close encounter like this would cause a tidal disruption event, which would break up the star and stop gas from flowing into the black hole’s accretion disc. The new research, though, makes this theory less likely to be true.

The scientists looked at data about the cosmic flare across the whole range of light, from radio to x-rays. One thing they noticed was that the power of x-rays went down quickly. X-rays are usually made when charged particles move around in strong magnetic fields, so this meant that the magnetic field around the black hole had changed quickly.

At the same time, both visible and ultraviolet light got brighter, which showed that parts of the black hole’s accretion disc were getting hotter. Neither of these things would happen if there was a disruption in the tides.

Instead, a magnetic reversal is the best way to explain the results. Researchers showed that when a magnetic reversal happens in a black hole’s accretion disc, the magnetic fields first weaken near the edges of the disc.

As a result, the disc might heat up more quickly. Because the magnetic field is weaker, charged particles give off fewer x-rays. Once the magnetic field has been turned around, the disc goes back to how it was before.

This is the first time that a galactic black hole’s magnetic field has been seen to flip. We know that these changes are possible, but we don’t know how often they happen. It will take more research to figure out how many times a galaxy’s black hole may switch places.

Source: amazingastronomy.thespaceacademy.org