Scientists have recently discovered strange lumpy terrain on Pluto that is unlike anything previously observed in the solar system. This terrain indicates that giant ice volcanoes were active relatively recently on the dwarf planet. The discovery was announced on Tuesday, and it sheds new light on the geological activity of Pluto.

The discovery was made by analyzing images captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft during its flyby of Pluto in 2015. The images showed that the surface of Pluto is covered in small, isolated hills that are surrounded by moats. These hills are believed to be the result of cryovolcanism, a process in which volcanoes erupt frozen materials like water, ammonia, or methane instead of molten rock.

The scientists believe that the cryovolcanism on Pluto was active within the last 10 million years, which is relatively recent in geological terms. The discovery of these ice volcanoes on Pluto is significant because it suggests that geological activity is not limited to larger planets like Earth and Mars, but can occur on smaller, icy bodies as well. Overall, this discovery provides new insights into the complex geology of the outer solar system.

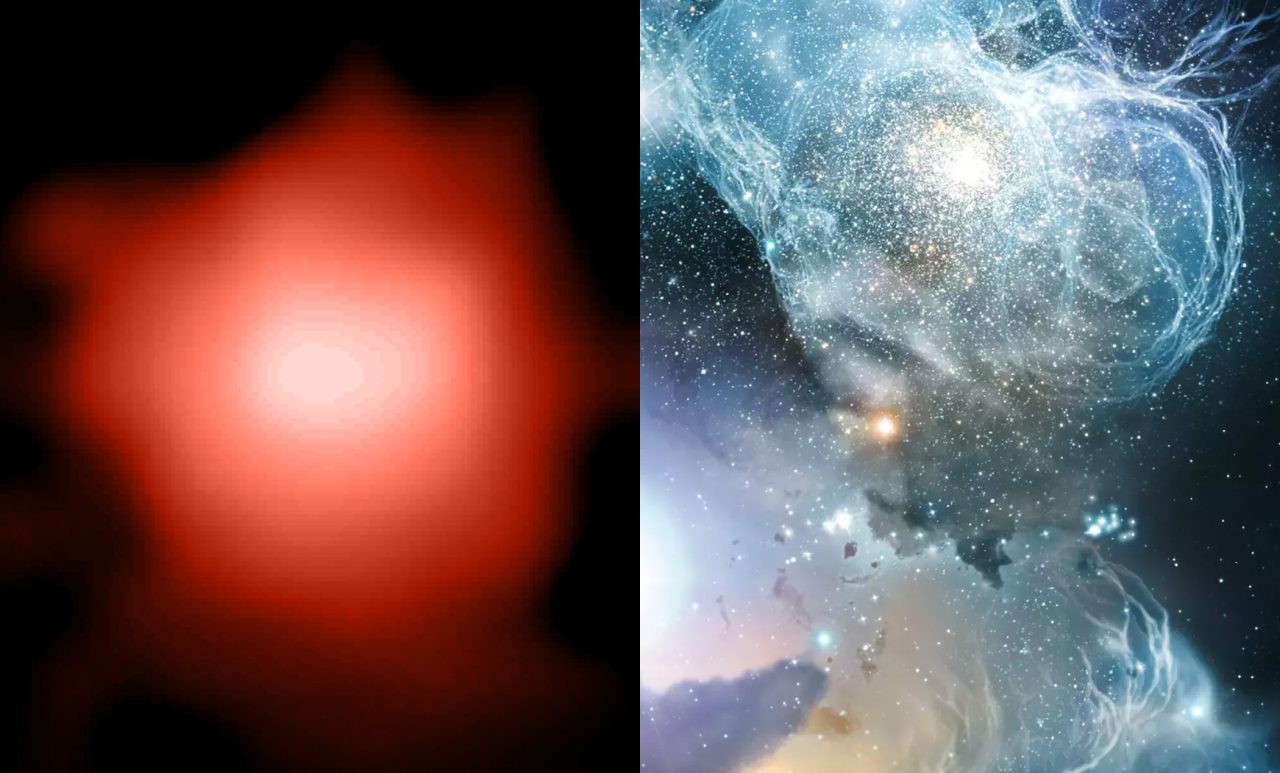

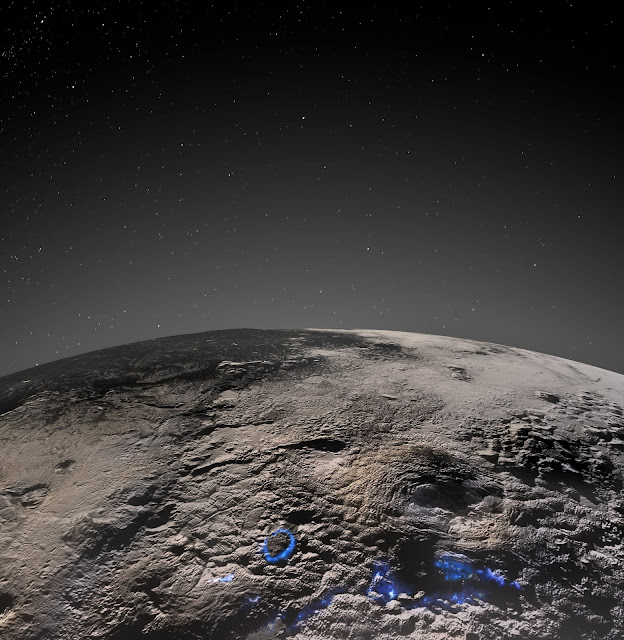

Perspective view of Pluto’s icy volcanic region. The surface and atmospheric hazes of Pluto are shown here in greyscale, with an artistic interpretation of how past volcanic processes may have operated superimposed in blue [Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer]

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications reveals that the interior of Pluto was hotter much later than previously believed. This is based on observations made by analyzing images taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which suggest that ice volcanoes were active on Pluto within the last few hundred million years.

Unlike traditional volcanoes that shoot lava into the air, ice volcanoes on Pluto are believed to have oozed a thicker, slushy icy-water mix or even possibly a solid flow like glaciers. While ice volcanoes were already thought to exist on several moons in the solar system, Pluto’s ice volcanoes look different from anything else observed in the solar system.

According to Kelsi Singer, a planetary scientist at Colorado’s Southwest Research Institute and study author, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when these ice volcanoes were formed. However, based on the absence of impact craters in the region, it is possible that the ice volcanoes are still forming even today. This discovery provides new insights into the geology and history of Pluto, and suggests that geological activity can occur on smaller, icy bodies in the outer solar system.

‘Extremely significant’

Lynnae Quick, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center specialized in ice volcanoes, said the findings were “extremely significant”.

Perspective view of Pluto’s icy volcanic region [Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Isaac Herrera/Kelsi Singer]

“They suggest that a small body like Pluto, which should have lost much of its internal heat long ago, was able to hold onto enough energy to facilitate widespread geological activity rather late in its history,” she told AFP.

“These findings will cause us to re-evaluate the possibilities for the maintenance of liquid water on small, icy worlds that are far from the Sun.”

David Rothery, professor of planetary geosciences at The Open University, said “we don’t know what could provide the heat necessary to have caused these icy volcanoes to erupt”.

The study published in the journal Nature Communications identified several ice volcanoes on Pluto, including the Wright Mons, which is estimated to be around three miles high and 90 miles wide. The Wright Mons has a similar volume to one of Earth’s largest volcanoes, Mauna Loa in Hawaii.

The discovery of these massive ice volcanoes on Pluto provides new insights into the geological activity of icy bodies in the outer solar system. The fact that they were active relatively recently suggests that Pluto’s interior may still be warm, and that geological activity may still be occurring on the dwarf planet. This finding challenges previous assumptions about the geological activity of smaller bodies in the solar system and expands our understanding of the processes that shape the surfaces of these distant worlds.

Rothery told AFP he had been to Mauna Loa and “experienced how vast it is”.

“This makes me realize how big Wright Mons is relative to Pluto, which is a much smaller world than our own.”

The analyzed images were taken when the New Horizons—an unmanned nuclear-powered spacecraft about the size of a baby grand piano—became the first spaceship to pass by Pluto in 2015.

It gave the greatest insight yet into Pluto, which was long considered the farthest planet from the Sun before it was reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006.

“I love the idea that we have so much left to learn about the solar system,” Singer said.

“Every time we go somewhere new, we find new things that we didn’t predict—like giant, recently-formed ice volcanoes on Pluto.”