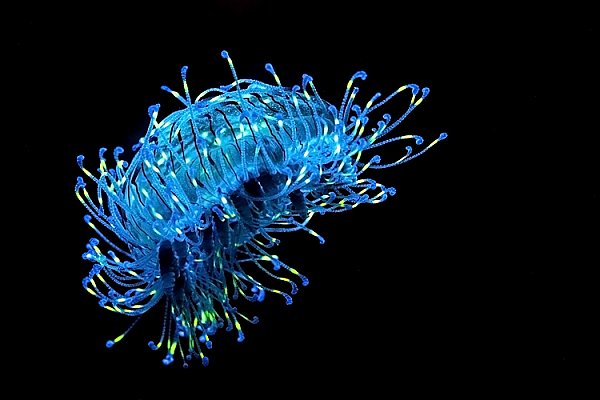

On the streets of Kannoura, a quiet seaside village on the Japanese island of Shikoku, there’s a distinct absence of the bright lights, towering buildings, and bustling pace that are characteristic of the country’s urban centers. “It’s the kind of place that could easily escape your attention if, say, you spaced out for a couple of minutes while driving past,” says underwater photographer and naturalist Tony Wu. But beneath the surface of Kannoura’s coastal waters, there are lights and activity aplenty. Here, the whimsically named flower hat jelly (Olindias formosus) brightens the murky depths with its neon halo of fuchsia and lime-green tentacles, the green segments of which fluoresce and function as glowing lures.

Fluorescence is a common strategy for producing conspicuous coloration in the world’s oceans, where the spectrum of penetrating light quickly narrows to a monochromatic blue. By absorbing blue photons and converting their energy into longer wavelengths of green, yellow, orange, and red light, ocean-dwelling species including corals, crustaceans, jellies, fireworms, and even some fish create contrasting colors that seem to glow against their dark backgrounds. Scientists have proposed a wide range of functions for this fluorescence, the most common of which include communication, protection from UV radiation, and providing usable light for symbiotic algae. In most species, however, these hypotheses have never been tested.

In 2015, a team of scientists led by Steven Haddock from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute set out to test the hypothesis that flower hat jellies use their fluorescent tentacles to attract prey. Through a series of laboratory experiments, the team observed that juvenile rockfish in the genus Sebastes were significantly more attracted to the jelly’s tentacles in lighting conditions where the fluorescence was visible. Additionally, under these lighting conditions, the fish were far more interested in the flower hat jellies than they were in non-fluorescing mimic jellies that were hand-crafted by the scientists and affectionately termed “blobjects.”

Having conclusively demonstrated that flower hat jellies use their fluorescent tentacles as lures to attract prey, the scientists began to wonder why the strategy worked. Their best guess is that the fish mistake the jellies’ glowing, green tentacles for algae, since the chlorophyll in algae is also naturally fluorescent. Algal tufts and mats often emit red fluorescence on reefs, and chlorophyll can even fluoresce from within the guts of animals that have recently eaten an algal meal. “Herbivorous prey may be attempting to find algae and be attracted by long-wavelength fluorescent pigment that would normally indicate the presence of chlorophyll,” they wrote, “while carnivorous prey could be searching for gut fluorescence.” None of this matters to the flower hat jelly, of course, as long as there is a steady stream of prey lured in by its flamboyant display.