The Valley of the Golden Mummies is the largest cemetery in Egypt dating back to Greco-Roman times.

It revealed around 250 mummies and most of them are aristocracies who lived in the Bahariya Oasis ( in the Western Desert of Egypt), during Greco-Roman times.

Egyptologist Zahi Hawass observed amazing flashes in 1996 coming from the bottom of a hole in a desert oasis in Egypt. This resulted in the discovery of many graves containing Greco-Roman corpses, all of which had incredible golden decorations.

Greco-Roman mummies

The Valley of the Golden Mummies is located 15 minutes from El Bawiti, in the Bahariya Oasis, about 400 kilometers from Cairo.

The Middle Kingdom is when the ancient Egyptian kings first became interested in this green dot in the middle of the desert, even though there are indications that a Paleolithic population formerly lived there. There, nomads and trade routes met, becoming a defensive enclave of the western borders.

Bahariya flourished most especially from the 26th dynasty and after the arrival of Alexander the Great and the Ptolemies.

The majority of the mummies found date to the Greco-Roman era (4th century BC–4th century AD), when the oasis was a major hub for wine exportation to the rest of the Nile Valley.

Hawass’ excavation revealed that the majority of the artisans and merchants that made up the oasis’s population had been interred in family pantheons that had amassed mummies of men, women, and children of varying ages over time. These are the Golden Mummies, who are magnificently attired in lovely cartonnage and masks that have been coated in thin layers of gold on stucco.

Egyptian and Greek elements

In the Greco-Roman era, mummification placed a strong emphasis on the mummy’s outward appearance. After being empty, the corpse was strengthened with wood or reeds and heavily coated with glue.

“You could still smell the resin used,” Hawass notes, recalling the moment he entered the tombs. Later, they would wrap the mummy in a linen bandage formed of intricate geometric patterns that gave it a sense of depth.

On occasion, the body and face of the deceased were painted and plastered with a cardboard model made of papyrus to create a burial mask. This was coated with delicate layers of gold in the case of affluent households.

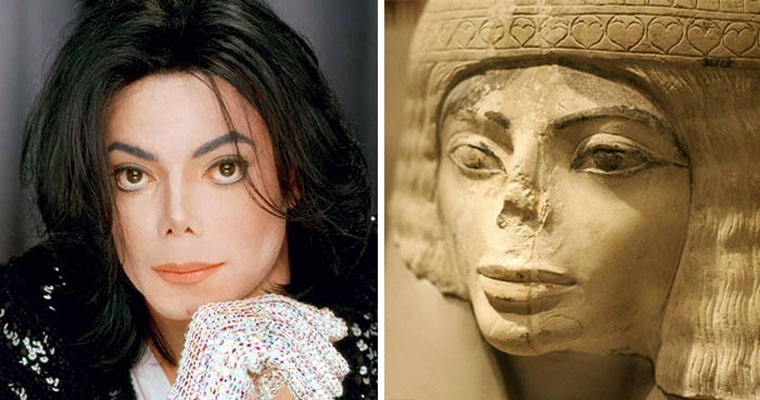

A stunning fusion of Egyptian and Greek elements may be seen in the bandages and masks of the Bahariya mummies.

Greco-Roman hairstyles were represented alongside images of ancient Egyptian gods, such as Isis, Anubis, and Horus. A female mummy found in a wooden sarcophagus had a stele at her feet that showed the deceased dressed in a Roman style and heading for the threshold of a door that would lead her to resurrection.

On the faces of several mummies, there were some made of glass, marble, or obsidian. These represented the eyes and eyelids and gave the deceased’s gaze vitality.

Mummies from the less favored classes of the oasis have been discovered in extremely poor conditions of preservation; after mummification, they were wrapped carelessly, and they were not placed inside any sarcophagus in the tombs.

There have also been discovered ceramic anthropomorphic sarcophagi, and occasionally poignant components can be seen. A female mummy, for instance, whose face was turned to the side so she could look at her husband’s mummy, who was resting next to her and had passed away earlier.

Tombs and grave goods

The majority of the unearthed tombs share a common structure. There are access steps leading to a small room where the body of the deceased was received.

After that, a narrow passageway leads to the lateral niches where the bodies were placed. In these tombs, which resemble a sort of catacomb, the mummies were just stacked high.

Some tombs show the god Anubis weighing the heart of the deceased alongside the feather of Maat before Osiris as decoration.

Statues of mourners and of the god Bes, protector of the home, have been found in grave goods such as offering vessels with remains of wine, food, and bronze, silver, copper, faience, and ivory jewelry.

Coins from the Greco-Roman period have also been found, one of them from the reign of the famous Cleopatra VII.

Among the most notable finds is the limestone sarcophagus that hid the mummy of Bahariya’s 26th dynasty governor, Djed-Khonsu-euf-Ankh, and the mummies of his wife Nesa II, his brother, and his father.

The tombs of Ta-Nefret-Bastet, Ped-Ashtar, and Thaty are from the same period and were looted during Roman times and were later reused.

The Valley of the Golden Mummies is one of the most important discoverable sites of Egypt’s Greco-Roman period, and its study is still far from over. In the words of Hawass, the excavation in the Bahariya area could last decades and is expected to discover more than 10,000 mummies during its course.

Archaeologist Mohammed Ayadi cleans some of the golden mummies found at Bahariya Oasis. Photo: AP

View of the oasis of Bahariya, in Egypt, in the vicinity of which the Valley of the Golden Mummies was discovered. Photo: iStock

Sarcophagus belonging to the brother of the governor of Bahariya during the 26th dynasty, discovered in 2004. Photo: AP

Mummies discovered in 2004 in the Valley of the Golden Mummies. Photo: AP

Src: kenhthoisu.net