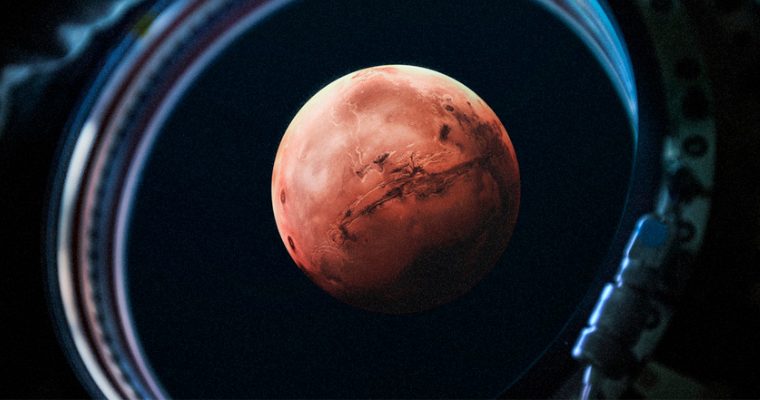

Astronomers have arrived at a planet that may have lost its atmosphere as a result of a collision with a big object for the first time.

A team of astronomers has identified a planet similar to Earth that may have lost some of its atmosphere two hundred thousand years ago due to a collision. Only 95 light-years away from Earth, MIT, National University of Ireland Galway, and Cambridge University astronomers discovered evidence of the huge collision in a nearby star system. The HD 172555 star is around 23 million years old, and astronomers believe its dust indicates a recent collision.

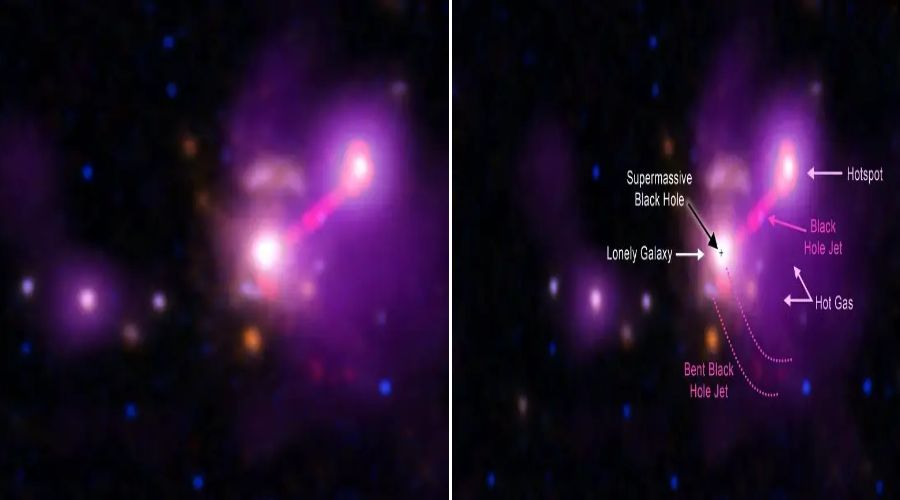

Massive impacts, according to a research published in the journal Nature, are responsible for planets like the early Earth reaching their final mass and achieving long-term stable orbital arrangements. An important prediction is that debris will be generated by these hits. The researchers discovered a carbon monoxide gas ring co-orbiting with dusty debris around HD172555 between six and nine astronomical units — a zone akin to the outer terrestrial planet area of our Solar System.

The strange makeup of the star HD 172555’s dust, which appears to contain a significant amount of unusual components in grains much smaller than astronomers would anticipate, is what draws astronomers to it. In order to look for carbon monoxide traces orbiting nearby stars, Tajana Schneiderman, a doctoral student at MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, examined data from Chile’s Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA).

The 66 radio telescopes that make up the ALMA observatory can be moved closer or farther apart to change the image resolution.

“Carbon monoxide is frequently the brightest and hence the easiest to discover gas while trying to investigate gas in debris discs. Since HD 172555 was an interesting system, we reexamined the carbon monoxide data for it, according to Schneiderman. After carefully examining the data, the researchers discovered carbon monoxide, which accounted for 20% of the carbon monoxide detected in Venus’ atmosphere.

Massive amounts of gas were spinning very near to the star, at a distance of about 10 astronomical units, or 10 times the distance between Earth and the sun. Scientists examined a number of explanations to account for the massive volume of gas that encircled the star.

Both the theory that the gas was created by the remnants of a young star and the theory that it was created by a belt of nearby ice asteroids were disproved by astronomers. The gas was a consequence of a significant collision, which the experts believe to be the most likely explanation.

It is the only scenario that can explain all the characteristics of the data. In systems of this age, we anticipate gigantic repercussions, and we anticipate that these impacts will be relatively common. The timelines, age, and morphological and compositional limitations are all consistent. In this system, the only probable process that may create carbon monoxide is a massive impact, Schneiderman said in a statement.

The team hypothesizes that the gas was discharged by a catastrophic collision at least 200,000 years ago, which is recent enough for the star not to have completely destroyed the gas. According to the amount of gas, the impact was likely massive, involving two protoplanets around the size of Earth.

According to astronomers, the impact was so violent that a piece of one planet’s atmosphere was blown away, resulting in the gas observed today.