A robotic mission to orbit Uranus. A probe that can land on a potentially life-supporting moon of Saturn. And a better plan for astronauts to do high-quality science on the moon.

These are among the top priorities outlined in a new report from an influential group that’s advising NASA on where to boldly go in the next decade, from 2023 to 2032.

Every ten years, the prestigious National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine brings together committees of space experts to survey the field of planetary science and reach a consensus on the best way for NASA to explore strange new worlds.

Some of the items on their latest wishlist sound familiar, but others are brand new. And while the report paints an optimistic picture of the field overall, there are hints of concern about future budget constraints.

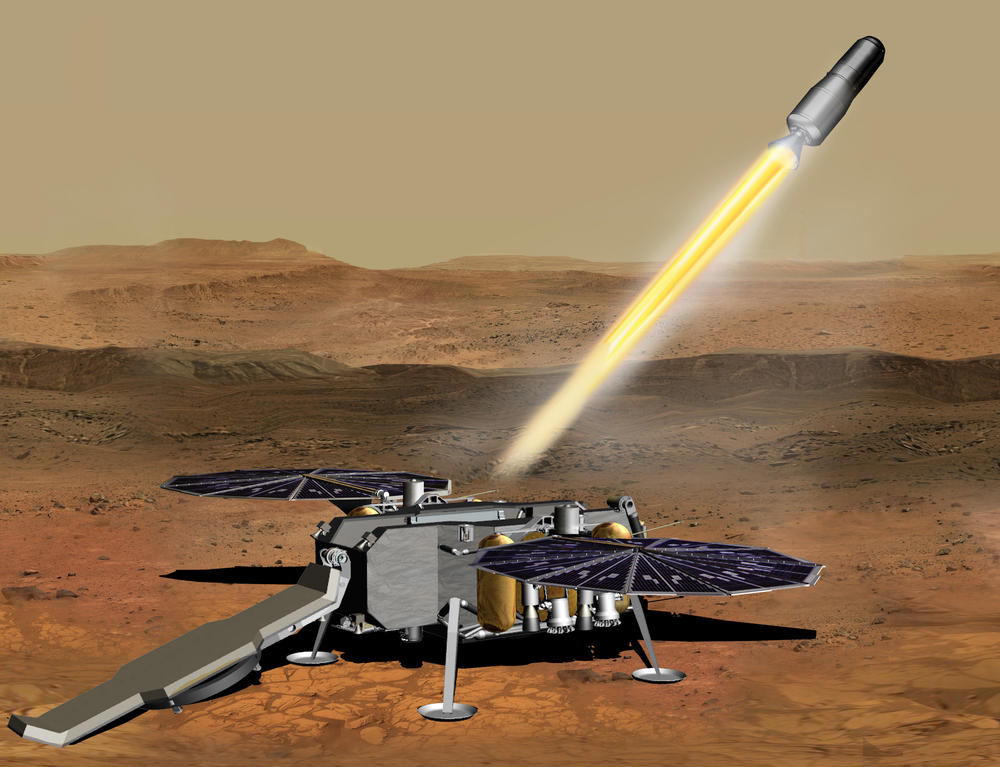

Retrieving Mars rocks is “highest scientific priority”

The last time around, in 2011, expert advisers told NASA to gather an interesting selection of rocks on Mars and then work to bring those pristine samples back to Earth for chemical analyses. This could show whether the red planet ever had life. They also argued for a mission to Europa, a moon of Jupiter that seems to have an ocean of water beneath its icy surface.

NASA embraced those goals and has been making progress, but planetary scientists have started to worry that cost overruns might threaten the ability to visit other places in the solar system that beckon.

“Right now in planetary science in the U.S., we’re at record levels of funding,” says Casey Dreier, senior space policy adviser for The Planetary Society, a nonprofit that promotes space exploration. “But I think at the same time, we are being squeezed by two major missions, Mars Sample Return and Europa Clipper.”

Bringing home rocks from the red planet should remain “the highest scientific priority of NASA’s robotic exploration efforts this decade,” according to the new, 780-page report on the expert group’s findings.

“The committee strongly supports Mars sample return. It’s a concept that’s been around a long time, it has a great deal of scientific validity and support,” steering committee co-chair Philip Christensen of Arizona State University told NPR.

But the report also says if the price tag looks to rise substantially above $5.3 billion, or if the cost eats up more than around 35% of NASA’s planetary science budget in any given year, NASA should seek additional money from Congress rather than taking funds away from other worthy missions — like ones to Uranus and Enceladus.

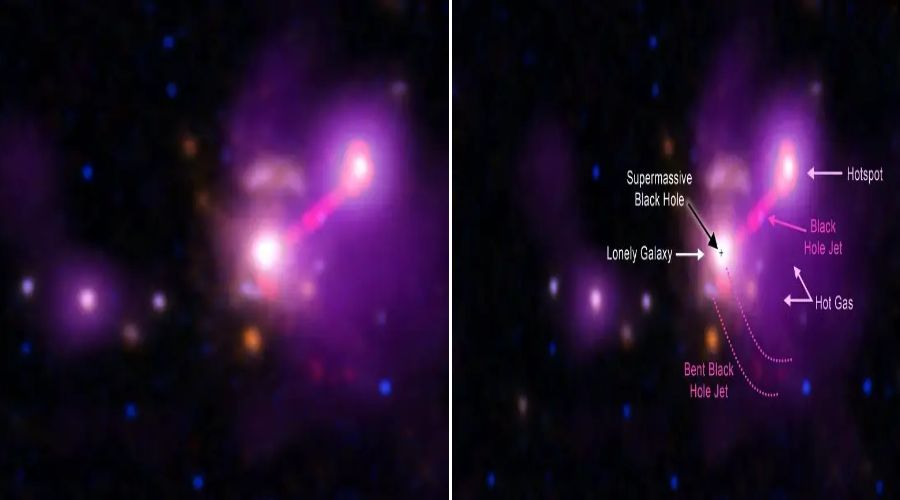

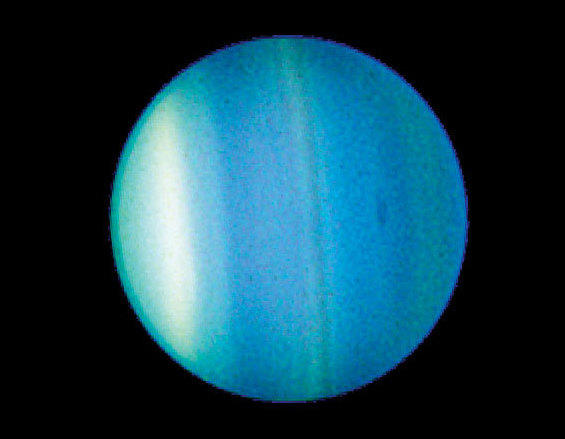

Ice giants could hold surprises

A trip to Uranus could help scientists understand ice giants.

Unlike rocky planets like Mars and gas giants like Jupiter, the ice giants Uranus and Neptune have never been studied with a dedicated mission to orbit and study them.

Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, has only ever been visited by NASA’s Voyager 2 probe, which flew by in 1986, coming within about 50,000 miles.

In recent years, detections of planets in alien solar systems show that ice giant planets are “likely the most common class of planets in the universe,” says Robin Canup of the Southwest Research Institute, who co-chaired the steering committee. “We saw this mission as delivering absolutely transformative, breakthrough science because we know so little about these systems. We are sure there are going to be lots of surprises once we get there.”

An ocean world could have evidence of life

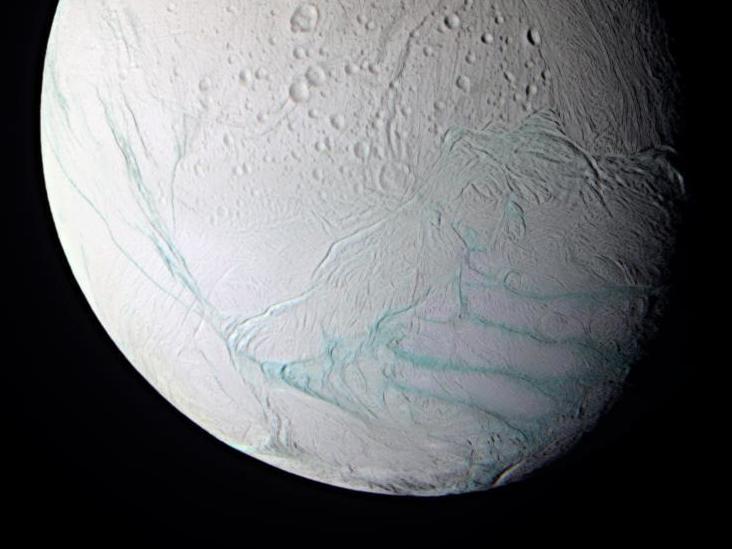

Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons, is another scientifically compelling destination.

It’s thought to have an ocean of liquid water under an icy crust, just like Europa, but this moon sends plumes of that material out into space, making it easier to obtain samples that originated deep within. The new report recommends sending a probe that could arrive there in the early 2050’s, land on the surface and search for evidence of life in fresh plume material that rains down on it.

“Enceladus is the logical candidate to go to try to look for evidence of life today,” says Christensen. “In terms of the ocean worlds, it’s by far the most active and the easiest to access.”

Making it to the moon again

The advisers say NASA needs to get serious about doing science in its multi-billion effort to return astronauts to the moon, called the Artemis program.

They point out that the failure to do this so far means the scientific return of the astronauts’ initial trips “will not be as significant as it could be, and may be minimal.”

“We see the Artemis program as being aspirational and transformative, and we want it to be accompanied by transformative science,” says Canup.

But the group found there’s a lack of organization and accountability at NASA for working high-priority science into the planning for moon landings. Planetary exploration has been done for decades with robots, and it’s separated from human spaceflight within the agency’s organizational structure.

“Let’s do great science at the moon,” says Christensen, and bring “the robotic and the human sides of NASA together into a really strong partnership.”

Protecting earth and other priorities

The report runs through a bevy of smaller missions around the solar system that have merit, such as visits to the dwarf planet Ceres and to Titan, the largest moon of Saturn.

And it gives a notable shout-out to the effort to protect Earth from potentially hazardous space rocks.

NASA should “fully support” a telescope, called the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, which is designed to search for these dangerous rocks, the report says. That telescope has recently faced budget cuts and delays.

“Protecting Earth is important,” says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at Caltech who served on the report’s steering committee, “and we can achieve good science while doing it.”

Source: gpb.