A team of paleontologists has found the remains of a prehistoric bird that lived 90 million years ago (Cretaceous period) in the Canadian Arctic.

An artist’s conception of Tingmiatornis arctica’s possible environment 90 million years ago, characterized by volcanic activity, a freshwater bay, turtles, fish, and champsosaurs. Image credit: Michael Osadciw, University of Rochester.

The team, led by University of Rochester Professor John Tarduno, has identified the well-preserved specimen as a new genus and species, which has been named Tingmiatornis arctica.

“The genus name is from ‘Tingmiat,’ which in Inuktitut references ‘those that fly.’ The species name makes reference to the high Arctic provenance of the holotype and referred material,” the researchers explained.

“Tingmiatornis arctica would have been a cross between a large seagull and a diving bird like a cormorant, but likely had teeth,” Prof. Tarduno said.

The team’s findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, add to previous fossil records the authors uncovered from the same geological time period and location in previous expeditions.

Taken together, these fossils paint a clearer picture of an ecosystem that would have existed in the Canadian Arctic during the Cretaceous period’s Turonian age, which lasted from 93.9 to 89.8 million years ago.

“Before our fossil, people were suggesting that it was warm, but you still would have had seasonal ice,” Prof. Tarduno said.

“We’re suggesting that’s not even the case, and that it’s one of these hyper-warm intervals because the bird’s food sources and the whole part of the ecosystem could not have survived in ice.”

From the fossil and sediment records, Prof. Tarduno and co-authors were able to conjecture that Tingmiatornis arctica’s environment in the Canadian Arctic would have been characterized by volcanic activity, a calm freshwater bay, temperatures comparable to those in northern Florida today, and creatures such as turtles, large freshwater fish, and champsosaurs.

“The fossils tell us what that world could look like, a world without ice at the Arctic. It would have looked very different than today where you have tundra and fewer animals,” said co-author Richard Bono, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rochester.

The Tingmiatornis arctica fossils were found above basalt lava fields, created from a series of volcanic eruptions.

Researchers believe volcanoes pumped carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere, causing a greenhouse effect and a period of extraordinary polar heat. This created an ecosystem allowing large birds, including Tingmiatornis arctica, to thrive.

An artist’s rendering of Tingmiatornis arctica. Image credit: Michael Osadciw, University of Rochester.

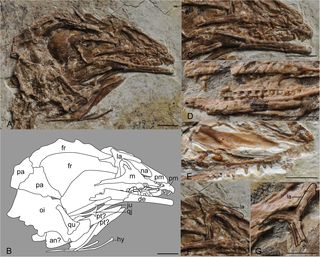

Prof. Tarduno and his colleagues unearthed three bird bones: part of the ulna and portions of the humerus, which, in birds, are located in the wings.

From the bone features, as well as its thickness and proportions, they were able to determine the evolutionary relationships of Tingmiatornis arctica as well as characteristics that indicate whether it likely was able to fly or dive.

“Fossils of Tingmiatornis arctica, while well-preserved, are few in number thus limiting inferences about the anatomy and ecology of this species. From the bone cortex thickness and proportions of the humerus, Tingmiatornis appears to be volant and likely a diving taxon like Pasquaornis,” the authors explained.

Previous fossil discoveries indicate the presence of carnivorous fish such as the 0.3-0.6 m-long bowfin.

Birds feeding on these fish would need to be larger-sized and have teeth, offering additional clues to Tingmiatornis arctica’s characteristics.

“Based on complete skeletons of the bowfin, Amia calva, as a most conservative estimate, the amiid fish known at the Arctic locality would be roughly 0.3-0.6 m long. This suggests these fish may have been able to out-compete birds below the size of Tingmiatornis arctica, if, as we propose, Tingmiatornis arctica was a diving bird potentially feeding on the fish documented in the Axel Heiberg fossil assemblage,” Prof. Tarduno and co-authors said.

“That Tingmiatornis arctica foraged at night also cannot be excluded considering that one potential modern analogue, the western grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis), is known to nocturnally forage while in its wintering habitats.”

“If Tingmiatornis arctica lived in the Arctic during the winter months, it would have experienced prolonged periods of twilight in addition to approximately 2 months of total darkness each year.”

Source: sci.news