The Cassini spacecraft, operated by NASA, is dying. The 13-year orbit of Saturn by the nuclear-powered spacecraft resulted in the return of hundreds of thousands of photographs. The images show up-close views of the gaseous giant, its well-known rings, and its mysterious moons, including Titan, which has its own atmosphere, and ice Enceladus, which has an ocean beneath its surface that may contain microorganisms.

To prevent Cassini from crashing into and contaminating any of those hidden oceans, the space agency has directed the craft, which is running out of fuel, onto a crash course with Saturn.

“As it makes these five dips into Saturn, followed by its final plunge, Cassini will become the first Saturn atmospheric probe. It’s long been a goal in planetary exploration to send a dedicated probe into the atmosphere of Saturn, and we’re laying the groundwork for future exploration with this first foray.” Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL, said in a press release.

These last passes will reveal new data about Saturn, its atmosphere and clouds, the materials making up its rings, and the mysterious gravity and magnetic fieldsof the gas planet.

“It’s Cassini’s blaze of glory. It will be doing science until the very last second.” Spilker previously told Business Insider.

Gravity from Titan, Saturn’s planet-sized moon, plays a key role in Cassini’s final orbits. NASA is using the force to bend Cassini’s course, a task that would otherwise require large amounts of fuel.

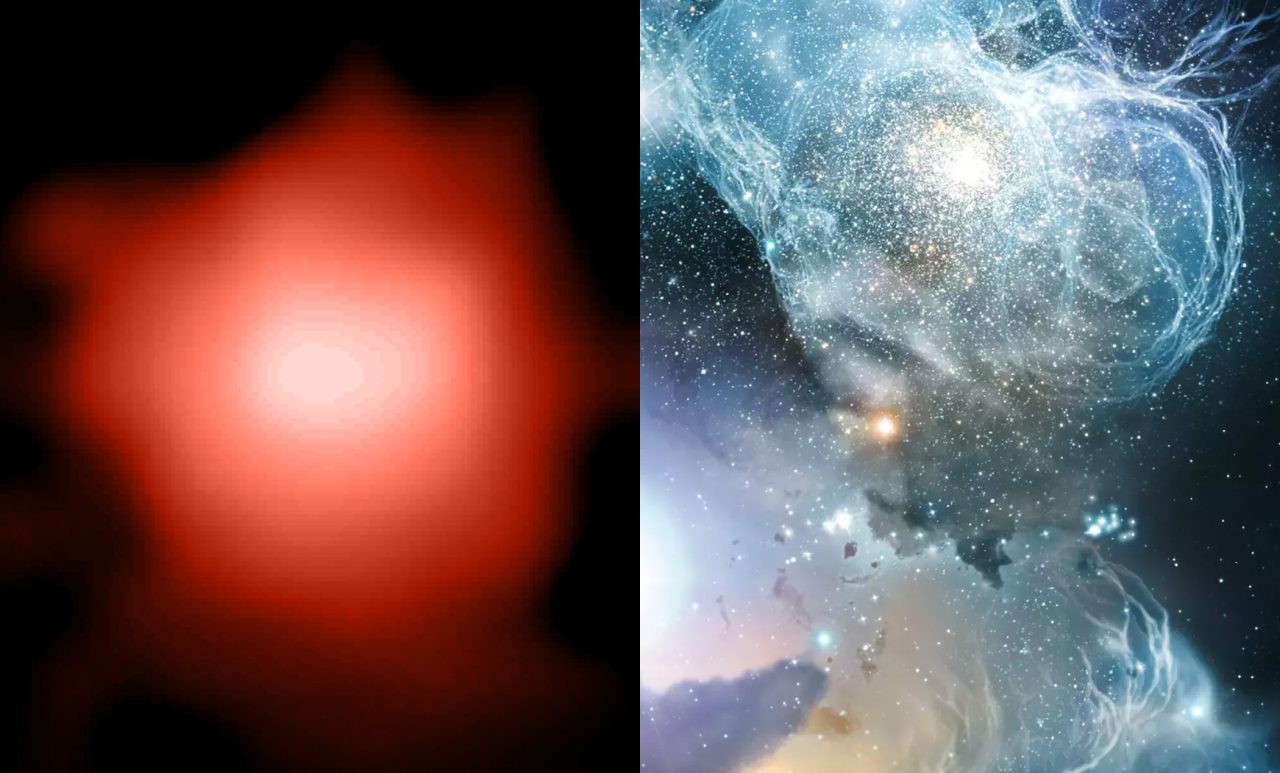

These two views of Titan show the new details about the moon’s surface – including clouds and hazes in its atmosphere – that Cassini has revealed:

The first of the probe’s final five orbits took it between the rings and the planet itself. Data from that fly-by is being sent back to NASA today.

NASA hopes this closest-ever brush with Saturn will reveal new components of its atmosphere, which is believed to be about 75 percent hydrogen, with most of the rest being helium.

The clouds on Saturn look like strokes from a cosmic brush because of the wavy way that fluids interact in Saturn’s atmosphere.

So far, scientists have been unable to discern any tilt between Saturn’s magnetic field and its rotation axis. That contradicts our understanding of magnetic fields, and makes it impossible to know exactly how long Saturn’s days are.

Before getting to the Grand Finale stage, Cassini was able to capture this view of Saturn’s moon Prometheus inside Saturn’s F ring:

The images were obtained using Cassini’s narrow-angle camera, at a distance of about 777,000 miles (1.25 million km). To capture the image above, Cassini gazed toward the rings beyond Saturn’s sunlit horizon. Along the limb (the planet’s edge) at left can be seen a thin, detached haze. This haze vanishes toward the right side of the scene.

On its last dives through the rings, Cassini will also be able to analyse samples of Saturn’s rings on its last dives. That will help scientists figure out how dense they are and better understand what they’re made of.

In the photo, the light of a new day on Saturn illuminates the planet’s wavy cloud patterns and the smooth arcs of its vast rings. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 10 degrees above their plane.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft looks toward the night side of Saturn’s moon Titan in a view that highlights the extended, hazy nature of the moon’s atmosphere. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometres) from Titan.

Source: sci-nature.vip